Biltmore Hotel

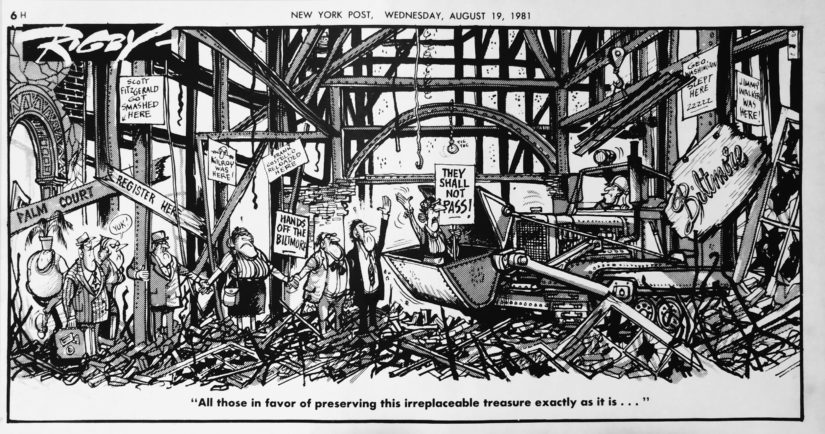

The loss of the Biltmore Hotel became an example of the danger of making deals with developers in the name of preservation.

Located across the street from Grand Central Terminal, the Biltmore Hotel was built in 1913 as part of the Terminal City Development, a vast complex of hotels and office buildings connected to the terminal and all owned by The New York State Realty and Terminal Company, a division of The New York Central Railroad. The contract for design and construction, first awarded to Reed and Stem, was later taken over by Warren & Wetmore, the noted designers of Grand Central Terminal, among other important projects.

The 26-story neo-classical hotel featured a “stone base with arched openings, a gray brick mid-section and terracotta loggia and projecting cornice.”1 Its H-plan allowed almost all of its rooms outside exposure and it was one of the first buildings in New York City to use air rights, making the hotel significantly taller than surrounding buildings at the time.2 Among its well-known interior features was a direct connection to Grand Central Terminal, one of the first indoor swimming pools and Turkish baths, rooftop gardens on the sixth floor setback, and a Palm Court with a golden timepiece made famous in popular culture by the saying, “Meet me under the clock.” In the early 1980s, after an unsuccessful attempt to designate the exterior and several of the interiors, the Biltmore Hotel was stripped to its steel structural frame and redesigned as an office building. The redesigned building is known as 335 Madison Avenue, and the original Biltmore Hotel clock is still extant in the building’s lobby. The Guastavino-tiled tunnel connecting the hotel to Grand Central Terminal also survives, an entrance to which can be seen on East 44th Street.

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission never designated the Biltmore Hotel as a New York City Landmark. The building was gutted to its structural steel frame and rebuilt in its current state with red granite and glass.

New Year's Eve, 1913: Biltmore Hotel opens.

Late 1970s: Hotel acquired by Paul and Seymour Milstein.

August 14, 1981: Hotel closes and demolition of its interiors begins.

September 16, 1981: Designation status rejected.

In the late 1970s, Paul and Seymour Milstein purchased the Biltmore Hotel with plans to convert it into an office building. At the time there was an increasing market for midtown office space and a slump in the hotel business. Speculative plans for the conversion of the hotel, in which it would be stripped to its steel structure and entirely rebuilt, were first reported in early 1981.3

Demolition began suddenly on August 14, 1981, taking many by surprise.4 In an intense three-day effort, preservation groups such as the Municipal Art Society (MAS) and New York Landmarks Conservancy (NYLC) rushed to get a court restraining order to stop what they called a "sneak attack" demolition as August 14 was a Friday. With a restraining order in place, the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) toured the building to determine if any interiors could possibly be designated along with the hotel's exterior, but found the interiors on the lower floors of the hotel, including the famed Palm Court, almost entirely demolished.5 Nevertheless, the LPC scheduled a public hearing to determine granting landmark status to the building's exterior and its remaining significant interiors, including the ornate ballroom on the 19th floor, its foyer, and the stairway in the lobby.6

At a September 1981 Landmarks Preservation Commission meeting, landmark designation was not granted to the Biltmore Hotel or any of its interior spaces. However, a private agreement was reached between the Milstein’s and the NYLC that would restore the Palm Court (with its famous clock) to a "reasonable approximation'' of its architectural shape and space as of August 13, the day before the hotel closed and demolition began.7 The agreement also retained several other features, but allowed the owners to demolish the ballroom and alter the exteriors.8 To assure the ''accuracy and adequacy'' of the restoration work on the Palm Court, the owners agreed to retain an architect acceptable to the NYLC to act as a consultant with the office building's designers.

Brendan Gill, chairman of the NYLC, hailed the agreement as an ''exceptional opportunity,'' saying it would ''far outweigh any of the possible alternatives'' and offered ''the most reasonable option to pursue.''9 Ralph C. Menapace, president of the Municipal Art Society, expressed strong support for the compromise but added that MAS would have preferred that the agreement be between the developers and the City of New York because the City had enforcement powers.10 This compromise was disclosed on September 9, days before the LPC designation hearing, and because it stressed that the agreement would not go forward if the Commission designated the exterior and the ballroom, it was one of the major reasons the LPC rejected designation.11

Two years later, the NYLC agreed to nullify the agreement requiring the owners to re-create portions of the Palm Court and other features of the hotel.12 The Milstein’s and the NYLC's appointed architect found that too much historic fabric had been lost and reconstructing the Palm Court would be a ''sentimental but artificial gesture.''13 Some contended, however, that substantial portions of the Palm Court had been lost after the NYLC reached its agreement with the Milstein’s, and many preservationists blamed the owners for this loss.14 Instead of pursuing court action, the NYLC accepted a settlement of $500,000 from the Milstein’s, to be used for educational purposes and prevent future similar "misfortunes."15

- Stern, Robert A. M., David Fishman, and Jacob Tilove. New York 2000: Architecture and Urbanism between the Bicentennial and the Millennium. New York: Monacelli Press, 2006. Pages. 474-475.

- Biltmore Hotel, N.Y.C. & H.R.R.C.O., 43rd St. & Madison Av., N.Y.C.: [detail drawing of vestibule in plan and sections]

Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library

Columbia University

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, New York 10027 - The Biltmore: New York- Photomechanical reproductions of photographs and illustrations

Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library

Columbia University

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, New York 10027 - The Biltmore by Warren and Wetmore

New-York Historical Society

170 Central Park West

New York, NY 10024 - News clippings and other information on the Biltmore Hotel

:

Anthony C. Wood Archives

New York Preservation Archive Project

174 East 80th Street

New York, NY 10075

Phone: (212) 988-8379

Email: info@nypap.org

- Oral History with Laurie Beckelman

New York Preservation Archive Project

174 East 80th Street

New York, NY 10075

Phone: (212) 988-8379

Email: info@nypap.org

- Box #1, “The Biltmore Hotel,” New York Preservation Archive Project office, Last Accessed on 12 January 2015.

- Laurie Johnston, “Biltmore Dismantling Stopped Again: For Hotel, Clock Runs Out,” New York Times, 17 August 1981.

- Randy Smith, “B of A’s Biltmore Hotel Deal may top $230M,” Daily News, 29 July 1981.

- David W. Dunlap, “Biltmore Closes, Surprising Guests,” New York Times, 16 August 1981.

- Katherine Schaffer and Paul La Rosa “Hotel may not be equal to some of its parts,” Daily News, 18 August 1981.

- David W. Dunlap, “Restraining Orders to Block Biltmore Demolition Expire,” New York Times, 19 August 1981.

- Paul La Rosa, “Biltmore’s fate to be decided today,” Daily News, 16 September 1981.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Sharon Rosenthal, “Biltmore Dispute Settled,” Daily News, 18 September 1981; “Board Refuses to List Biltmore as a Landmark,”. 20 September 1981; William G. Blair, “Accord Is Reached on Restoring Palm Court of the Biltmore Hotel,” New York Times, 10 September 1981.

- Martin Gottlieb, “Landmark Group Plans Uses for Biltmore Funds,” New York Times, 6 October 1983.

- Ibid.

- “Demolition Derby,” Daily News, 27 April 1987; Mark Liff, “Demolition Resuming,” Daily News, 9 May 1982.

- Martin Gottlieb, “Landmark Group Plans Uses for Biltmore Funds,” New York Times, 6 October 1983.