1973 Amendments to New York City’s Landmarks Law

In 1973, the Landmarks Law was amended to authorize the Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate the interiors of buildings as “interior landmarks” and to mark certain city-owned public open spaces as “scenic landmarks.” The amendment also permitted the LPC to deal with designation requests on a rolling basis instead of a previously instated three year interval between each six‐month period of hearings on new landmarks.

On April 19, 1965, New York City’s Mayor Robert Wagner signed the Landmarks Law. This legislation was designed to protect historic buildings and neighborhoods in New York City from unchallenged developments that threatened to destroy or fundamentally alter their character.[1] Preceding this law is the formulation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), appointed by Mayor Wagner in April 1962, advised by the Committee for the Preservation of Structures of Historic and Esthetic. Soon after, the commission started officially designating buildings as landmarks, and by 1963, it had evolved into a more formal city agency.[2] However, with the institution of the 1965 landmarks legislation, the Commission achieved official regulatory power to designate a building to be a “landmark” on a particular “landmark site” or to designate an area as a “historic district.” Landmark Status, by definition, means that a building so designated may not be altered without the approval of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.[3]

In December 1973, his successor, Mayor John Lindsay, signed legislation that amended the Landmarks Law to authorize the Commission to designate the interiors of buildings as “interior landmarks” and to mark certain city-owned public open spaces as “scenic landmarks.”[4] The amendment also permitted the Landmarks Preservation Commission to deal with designation requests on a rolling basis instead of a previously instated three year interval between each six month period of hearings on new landmarks.[5]

In its early years following passage of the NYC Landmarks Law, the Landmarks Preservation Commission was wading in largely uncharted waters.[6] During this time, the preservation law had limited the jurisdiction of the Commission to designating only the exterior of buildings or neighborhood districts over 30 years of age with either historical or architectural heritage.[7] Despite being included in the early draft of the Landmarks Law, interior landmarks designation was left out of the Bill ultimately approved by the City Council and Mayor Wagner in 1965, as the pre-law Commission was afraid to take on more work than it could handle.[8] This severely limited the Commission’s ability to protect culturally- and architecturally-significant interiors, such as the auditorium of Old Metropolitan Opera House, designed by Carrere & Hastings in 1903, which, despite vehement preservation efforts, was demolished in 1967.[9] At the same time, proposals were put forward to take down the interiors of Grand Central Terminal and the central staircase of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. [10]

Furthermore, while the Commission could and had previously designated cemeteries as landmarks, it lacked the authority to designate public parks as scenic landmarks. This inadequacy was particularly evident when a series of proposals for the expansion of the Metropolitan Museum of Art to add the Lehman Pavillion, located in a designated building in Central Park, was brought forward. Even in the face of community concerns about park encroachment, the Commission could only issue a report on the proposed design, not a certificate of appropriateness. The report itself was not published in the City Register, the official record of municipal hearings and actions[11], and was only brought to public attention after being stolen from the records of the Department of Parks and Recreation.[12] The Commission was also criticized for the designation hearing moratorium- a cycle of six-month "designating periods" followed by three-year hiatuses, considered insufficient to meet the increased demands for designation. [13] In January 1972, a series of articles were published in the New York Post that focused on these weaknesses of the 1965 Landmarks Law and questioned the apparent reluctance of the Commission to exercise its limited powers in the face of strong real estate resistance. [14]

Later in the same year (1972), Harmon Goldstone, then Chair of the Commission, submitted a statement to Mayor Lindsay on the work of the Landmarks Preservation Commission and raised several critical issues, including the proposal to regularize the hearing schedule.[15] The Mayor supported amendments to the Landmarks Law, stating that he was “... struck by the industry and judiciousness of its (LPC’s) members and staff.” and promising “...a more responsive Law, geared more closely to the needs of New York City in the 1970s.”[16] The revisions, drafted by the Municipal Art Society, were submitted to the Corporation Counsel for review. Following this, the legislation was introduced and sponsored by Majority Leader Thomas J. Cuite, Councilman Carter Burden, and Councilman Edward L. Sadowsky. In November 1973, the City Council voted after 25 representatives of prestigious organizations and community groups spoke in favor of the legislation at a public hearing before the council’s Charter and Government Operations Committee. [17] The only opposition presented was a letter from the New York Real Estate Board stating that the legislation would be an added restriction on private ownership and may prevent normal development in the city. [18] The legislation was subsequently passed by the Council by a vote of 36 to 0 with one abstention[19] and the Landmarks law was accordingly amended in 1973, with the revised provisions going into effect the following year. [20]

With the 1973 amendments, the NYC Landmarks Law, was updated to include scenic and interior landmark designations.[21] The legal definition of an “interior landmark” allowed the designation of an interior, thirty years old or older, which is customarily open or accessible to the public and has a special historical or aesthetic interest, heritage, or cultural characteristics. By law, interior spaces specifically used for purposes of religious worship were excluded from consideration to avoid First Amendment challenge based on the interpretation of the “customarily accessible to the public” clause. [22] For a “scenic landmark,” the requirement for designation was for any landscape feature, thirty years old or older, which has a special historical or aesthetic interest, heritage, or cultural characteristics of the city, state, or nation.[23] In addition, all commission reports on city-owned buildings were now required to be published in the City Record, The reports on privately-owned landmarks had been previously required to be made public, but those on city properties only had to be submitted to the Mayor and appropriate agencies. The amendment brought about greater transparency regarding the Commission’s stance on the plans for city-owned properties. The change also allowed administrative changes for the Commission to hold hearings and designations on a rolling basis by discontinuing the three-year hiatus, increasing the number of staff appointments for the Commission from 15 to 26, and increasing a budget increment from $300,000 to $450,000.[24]

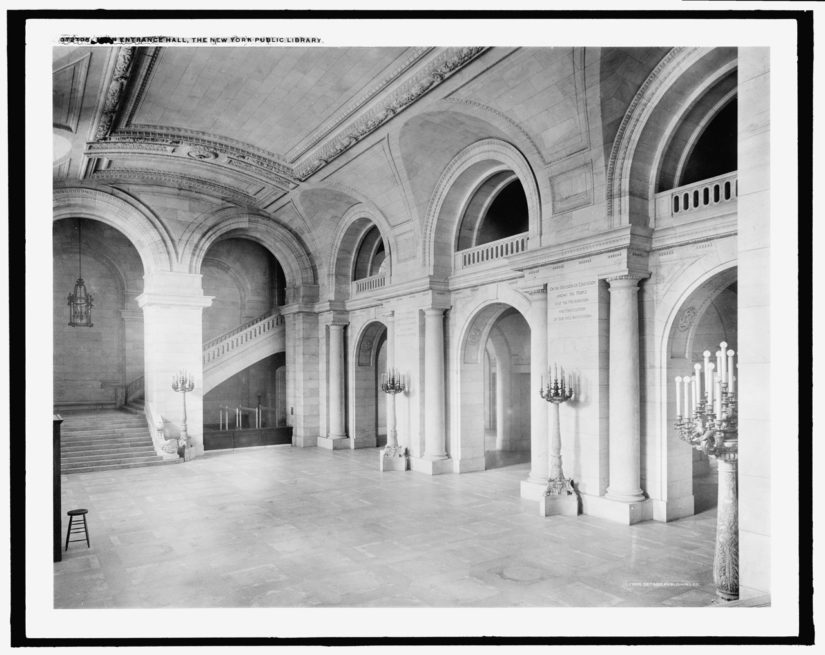

On November 12, 1974, the Landmarks Preservation Commission successfully designated three geographically contiguous items that would represent three new landmark categories.[25] The first- the three-story main lobby of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building situated at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street, which functions as the main branch of the New York Public Library, was distinguished as an Interior Landmark. The library’s interior spaces, designed by Carrere & Hastings, were described in the Commission's designation report as “...of monumental scale and outstanding quality [providing] a grand approach to the facilities of one of the finest libraries in the world.” [26] The second American Radiator Building at West 40th Street, dating from 1923 with a design by Raymond Hood, was designated as an individual landmark- the second-ever skyscraper designated by the Commission.[27] Finally, the third was Bryant Park, between 40th and 42d Streets, an important urban link between the two aforementioned landmarks that was designated as the first Scenic Landmark. The Commission called it “a prime example of a park designed in the French Classical tradition – an urban amenity worthy of our civic pride.”[28]

1962: Mayor Wagner appoints the first Landmarks Preservation Commission on the recommendation of the Committee for the Preservation of Structures of Historic and Esthetic Importance

1965: Mayor Robert Wagner signed the landmarks bill into law called the New York City Landmarks Law, Geoffrey Platt appointed as the Chair of the Landmarks Commission

1968: Harmon Goldstone succeeds Geoffrey Platt as the Chairman of the Landmarks Preservation Commission

1967: “Old” Metropolitan Opera House was demolished

1973: Mayor John Lindsay signed legislation that amended the Landmarks Law

1974: Designation of the Main Lobby of Stephen A. Schwarzman Building as the first interior landmark and Bryant Park as the first scenic landmark

[1] https://www.nypap.org/preservation-history/new-york-city-landmarks-law/, “New York City Landmarks Law”, The New York Preservation Archive Project, visited 6 July 2022.

[2] https://www.nypap.org/preservation-history/new-york-city-landmarks-law/, “New York City Landmarks Law”, The New York Preservation Archive Project, visited 6 July 2022.

[3] https://www1.nyc.gov/site/lpc/about/about-lpc.page, “History of LPC & the Landmarks Law”, NYC Landmarks Preservation, visited 6 July 2022.

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/1973/12/18/archives/metropolitan-briefs-justice-pfingst-loses-newtrial-plea-lindsay.html, “Metropolitan Briefs”, New York Times, 18 December 1973.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_City_Landmarks_Preservation_Commission#CITEREFSternMellinsFishman1995, “New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission”, Wikipedia, visited 6 July 2022.

[6] https://www.nypap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/320367933-Marjorie-Pearson-pdf.pdf, Pearson M., “The Goldstone Years”, The Commission Established (1965-1973), Page 46, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation, 2010.

[7] “Council to Weigh Tougher Landmarks Law”, Gratz R., n.d., October 31, 1973.

[8] https://www.nypap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/320367933-Marjorie-Pearson-pdf.pdf, Pearson M., “The Goldstone Years”, The Commission Established (1965-1973), Page 48, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation, 2010.

[9] “Council to Weigh Tougher Landmarks Law”, Gratz R., n.d., October 31, 1973.

[10] https://www.nypap.org/preservation-history/harmon-goldstone/, “Harmon Goldstone”, The New York Preservation Archive Project, visited 6 July 2022.

[11] https://www.nypap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/320367933-Marjorie-Pearson-pdf.pdf, Pearson M., “The Goldstone Years”, Page 47, The Commission Established (1965-1973), New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation, 2010.

[12] “Landmark Revamp Gets an OK”, Gratz R., n.d., November 2, 1973.

[13] “Landmark Revamp Gets an OK”, Gratz R., n.d., November 2, 1973.

[14] “ New Landmark Law is passed”, Gratz R., n.d., November 28, 1973.

[15] https://www.nypap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/320367933-Marjorie-Pearson-pdf.pdf, Pearson M., “The Goldstone Years”, The Commission Established (1965-1973), Page 49, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation, 2010.

[16] https://www.nytimes.com/1973/12/18/archives/metropolitan-briefs-justice-pfingst-loses-newtrial-plea-lindsay.html, “Metropolitan Briefs”, New York Times, 18 December 1973.

[17] https://www.nypap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/320367933-Marjorie-Pearson-pdf.pdf, Pearson M., “The Spatt Years”, Expanding a Mission and a Mandate (1974-1983), Page 56, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation, 2010.

[18] https://www.venable.com/files/upload/NYC_Administrative_Code_Landmarks_Preservation_and_Historic_Districts.pdf, “Chapter 3: Landmarks Preservation and Historic Districts, §§25-301 –25-322”, Title 25: Land Use, Administrative Code for the City of New York, visited 6 July 2022.

[19] https://www.nypap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/320367933-Marjorie-Pearson-pdf.pdf, Pearson M., “The Goldstone Years”, The Commission Established (1965-1973), Page 48, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation, 2010.

“Council to Weigh Tougher Landmarks Law”, Gratz R., n.d., October 31, 1973.

[20] https://www.nypap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/320367933-Marjorie-Pearson-pdf.pdf, Pearson M., “The Spatt Years”, Expanding a Mission and a Mandate (1974-1983), Page 57, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation, 2010.

[21] https://www.nytimes.com/1974/11/14/archives/3-new-sorts-of-landmarks-designated-in-city-landmarks-of-3-sorts.html, “3 New Sorts of Landmarks Designated in City”, Carroll M., The New York Times, November 19, 1974.

[22] https://www.nypap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/320367933-Marjorie-Pearson-pdf.pdf, Pearson M., “The Spatt Years”, Expanding a Mission and a Mandate (1974-1983), Page 57, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation, 2010.

[23] https://bryantpark.org/blog/history, “The Modern Bryant Park”, History, Bryant Park, visited 6 July 2022.

[24] https://www.nypap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/320367933-Marjorie-Pearson-pdf.pdf, Pearson M., “The Goldstone Years”, The Commission Established (1965-1973), Page 48, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation, 2010

“Council to Weigh Tougher Landmarks Law”, Gratz R., n.d., October 31, 1973.

[25] https://www.nypap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/320367933-Marjorie-Pearson-pdf.pdf, Pearson M., “The Spatt Years”, Expanding a Mission and a Mandate (1974-1983), Page 57, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation, 2010.

[26] https://www.nytimes.com/1974/11/14/archives/3-new-sorts-of-landmarks-designated-in-city-landmarks-of-3-sorts.html, “3 New Sorts of Landmarks Designated in City”, Carroll M., The New York Times, November 19, 1974.

[27] https://www.nypap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/320367933-Marjorie-Pearson-pdf.pdf, Pearson M., “The Spatt Years”, Expanding a Mission and a Mandate (1974-1983), Page 57, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (1962-1999): Paradigm for Changing Attitudes Towards Historic Preservation, 2010.

[28] https://bryantpark.org/blog/history, “The Modern Bryant Park”, History, Bryant Park, visited 6 July 2022.