George Calderaro

George Calderaro is the founding director of the Tin Pan Alley American Popular Music Project. He is a long-time communications professional and advocate for historic preservation.

George Calderaro has a rich history in New York City’s preservation and cultural sectors, and a career that highlights the intersection of preservation, community engagement, cultural history, and cultural memory.

In this interview, Calderaro recounts his career beginning with roles at museums like the New Orleans Museum of Art and the Studio Museum in Harlem, transitioning to the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) under Commissioner Laurie Beckelman during the David N. Dinkins administration. At LPC, as Director of Communications, he engaged with public testimonies and Certificate of Appropriateness hearings crucial for city-wide preservation decisions. His tenure at LPC exposed him to diverse community preservation efforts across the city, influencing his deep involvement in organizations like the Historic Districts Council. Calderaro was also locally involved with Community Board 1, advocating for landmark designations and community engagement projects in Lower Manhattan.

Calderaro’s dedication to preserving historic buildings led him to initiatives like the campaign to designate Tin Pan Alley as a landmark, a milestone achieved in 2019. This designation marked the recognition of Tin Pan Alley’s significance as the birthplace of American popular music, fostering collaborations with cultural institutions and diverse community groups to celebrate its legacy. As Founding Director of the Tin Pan Alley American Popular Music Project, his ongoing work preserves and promotes this rich cultural heritage through events and cultural initiatives, and underscores his commitment to cultural placemaking and historical education.

Q: Today is October 6, 2023, and this is Sarah Dziedzic interviewing George Calderaro for the New York Preservation Archive Project. Can you start by saying your name, and giving yourself a brief introduction?

Calderaro: I’m George Calderaro. I am the Founding Director of the Tin Pan Alley American Popular Music Project, and a board member of various preservation organizations.

Q: Thank you. I’m curious to hear a little bit about where you grew up and what your relationship to history was like.

Calderaro: I grew up in Stamford, Connecticut. I didn’t have a long relationship with history. It’s kind of shocking that Fairfield County, in general, and Stamford, among them, is not that involved with preservation. I went to the Historical Society, I knew the Stamford Museum, but my real introduction to preservation and New York City preservation, in particular, was after spending many years in communications roles in nonprofit organizations, mostly museums. I worked at the Landmarks Preservation Commission [LPC] in communications, in community relations, and that was my entrée to the preservation world. I was always passionate about architecture, and music, and art history, but I realized that the throughline through all of my interests was, in fact, history.

Q: What were some of the museums that you worked in.

Calderaro: I was first at the New Orleans Museum of Art. I went to Tulane, and was working there as my work/study job. Then I moved to New York and worked at the Neuberger Museum of Art at SUNY Purchase, and then went to the Studio Museum in Harlem. So I had about ten years in museums, and then went to the Landmarks Commission in the Dinkins administration, under Commissioner Laurie Beckelman.

Q: What was your interest in communications?

Calderaro: I am interested in learning and sharing what I know, and information. I really see communications as sharing, and I was really lucky to have been working always in nonprofit organizations, or government agencies, and particularly in museums. So it was very easy to be enthusiastic, and also to be learning at the same time.

Q: What was your awareness or relationship to New York City when you were growing up in Stamford?

Calderaro: We would come here all the time. Both my parents are New Yorkers. And Stamford, as you may know, is an express stop on the train, so we would come in regularly to go to the theatre, to go to museums. That was my exposure to the city. People say, “Oh you’re from Stamford, that’s New York.” And like, “No. Stamford is not New York.”

Q: Do you remember some of the museums that you were most interested in?

Calderaro: Particularly the Frick, the Met, Cooper Hewitt. My mom was an avid museum goer. We spent a lot of time.

Q: So let’s chat about how you ended up at the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Calderaro: I learned about it through, actually, my oldest friend in the world—another preservationist—Eve Kahn, who I grew up with in Stamford. And her mother, Renee Kahn, who I, among many others, consider the face, and voice, and the driving force of preservation in Stamford, Connecticut, if not all of Fairfield County. So Eve and I met in the fifth grade when we were nine or ten, or something like that, and we’ve been friends ever since. She went to Harvard, I went to B.U. She moved to New York, I moved to New York. We went to Paris—not together, all different times. But we’re great friends now. In fact, I nominated her for the board of the Victorian Society, and we’re both on that board. She is on the board of the Tin Pan Alley American Popular Music Project, where we’re closer than ever.

In any case, she was involved with preservation and knew Laurie Beckelman, and said, “There’s a communications job, and you’re a communicator,” and that was the connection. [00:05:00] And I went in there and I was pretty naïve about New York City preservation. But because of being the director of community relations at the NYC Landmarks Commission, you really are at the epicenter of preservation in the city. So I was working with everyone from the Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts, on whose board I now serve, and the Historic Districts Council [HDC], on whose board I now serve, among many other organizations, right down to the Mud Lane association in Staten Island [Mud Lane Society for the Renaissance of Stapleton]. So working with these wonderful, passionate, community preservationists in all five boroughs, was eye opening, and I’ve gotten more involved ever since.

Q: What made you move back to New York?

Calderaro: A man. No [laughs]. I graduated Tulane and I was done. I love New Orleans, but it was also a time in the ‘80s when the economy was foundering because of an economic dip caused by the oil industry, actually. So I had a good experience and several years in New Orleans––and a year in Paris through Tulane, as well–– and finally graduated in ‘86.

Q: What neighborhood did you live in?

Calderaro: I lived in Vieux Carré. I lived in the French Quarter.

Q: I mean in New York.

Calderaro: Oh, in New York [both laugh]. I lived in many neighborhoods. First on the Upper West Side near Columbia, where I work now, coincidentally, and then in the East Village, the West Village, Murray Hill. I live in Curry Hill now, on 28th Street, but not on Tin Pan Alley. I always tell people: this isn’t NIMBY. I didn’t work to get Tin Pan Alley designated as a landmark to protect my view, or anything that was, you know, personal. So various neighborhoods.

Q: I’m curious about how you felt about the transition from museums to the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Calderaro: It was an easy transition, in that it was about education, it was about culture, it was about celebrating art history. So it was a pretty easy transition. Perhaps too easy. I realized when Giuliani became mayor that I was not political enough for what he wanted, or what his administration wanted. I saw myself as a communicator, and a community relations person, and I was, for lack of a better word, too honest, in that if I knew something was going on, I would say it, and sometimes it ran afoul, perhaps, of what City Hall wanted. People don’t remember this, but Rudy Giuliani, in his brilliance and arrogance, offered severance to all two hundred and something thousand city workers when he came in. Said, “Whether you’re a custodian or a commissioner, you could all leave and get severance.” So those of us who (a) were not passionate about staying in that administration, and (b) thought we could get another job, left. And he did it in several cycles, too. I think he offered severance three times to the city workers. And so the third time, I said, “Okay. This is not right.” He was also condensing all of the press and communications functions, all under the Mayor’s Office, and a woman named Cristyne Lategano—who he may or may not have been having an affair with. You could look that up [laugh].

Q: I can’t even bear it imagine that. So is there an example of where you kind of “ran afoul” of what the city wanted you to say?

Calderaro: I really can’t think of anything that specific. It was just more of a––something that became, yes, uncomfortable. But there wasn’t one thing.

Q: Was there somebody in that role before you had it? [00:10:00]

Calderaro: Yes. Lisi De Bourbon succeeded me and she went on and she was in communications, I think, in the library—the New York Public Library, or the Brooklyn Public Library. The Brooklyn Public library [Queens Public Library], and I think she may still be there with Dennis Walcott. Tracie Rozhon was my predecessor. So there were people there, and I did have a small staff, including the current longtime commissioner of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, Sarah Carroll. She worked with me. She was a community relations liaison, and that’s going back to 1993, I think. And she is now, and has been for several years, the Chair of the Commission.

Q: Wow. Do you recall anything in particular that was landmark news at the time?

Calderaro: What were the hot––I remember the designations. Because since I was a community relations director and communications director, I would have to go to the hearings. So for example, just one example of a designation was Jackson Heights. That was a bit of a battle, in that Queens is not renowned for its preservation efforts. In fact, I think it has the lowest number of designations per capita. But that was just one. And then on Staten Island, St. George. It was lobbying, and community relations, and advocacy to have the community—you often think there are communities all over the city that are desperate for landmark designation and protection, and that’s absolutely true, but likewise, there are communities that are desperate not to be landmarked and not to have regulation. So there’s a balance.

Q: Are you communicating both ways, or are you communicating kind of the official statements of the—

Calderaro: Both ways. The process is the process. And what it means is what it means. Whether you’re talking about regulation, or you’re talking about tax benefits, or you’re citing examples and positive outcomes, it’s the same. The story is the story. You don’t have different—maybe that was my problem [laugh], and my lack of political finesse.

Q: The story is the story. So let’s talk about when you left. When you finally left, where did you decide to go?

Calderaro: I decided to leave, and two things happened. Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel said that, “Oh, well now you can help me with—” I think it was [work in preparation for] the 30th anniversary of the Landmarks Commission—we could look that up. It was in ’94, I think. So I worked with her as a consultant. And I was very grateful to her because I didn’t have something to go to, and I also got a chance to work side by side with the great Simeon Bankoff. Judy Janney, Simeon and I, you know, held down the fort at the Landmarks Preservation Foundation at that point. It’s now called the Historic Landmarks Preservation Foundation, I believe, under Barbaralee, who’s still going strong. And we’re on the verge of celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Landmarks Law. So I’m working with her and with Simeon—who I saw last night. So I went there, and that was one thing.

Another thing that momentously, for me, happened, was that the great Franny Eberhart, who was the first paid staff member of the Historic Districts Council, when I told her I was leaving, she said, “Oh great. You can join the board of HDC now.” And I said, “Great.” And I’m happy and proud to say I’m still on the board. We have to rotate on and off because of term limits, but I’ve always been involved, either as an advisor or board member. So I’m currently a board member at HDC. So those are two. And that started my board trajectory, [laughs] if you will.

Q: Yes. So we had talked before we started about your work around the Certificate of Appropriateness [C of A] element of the Landmarks Law. [00:14:59] So do you want to talk about how that was something you were focused on?

Calderaro: Yes. I had the privilege and responsibility of going to the—it’s now weekly, sometimes they were more frequent, sometimes less frequent––but the Certificate of Appropriateness hearings at the LPC, which were, as you probably know, endlessly fascinating. You know you had everyone from starchitects talking about their new developments. You’ve got Norman Foster talking about the skyscraper to go on top of the Hearst Building, to a woman in Cobble Hill, who wants to get her one window approved. And it all goes—obviously, if something is not approved at the staff level, it has to go to the C of A. So obviously, every window does not go to the C of A, but you do have this incredible mix. I do remember one woman who was on the same docket as the Empire State Building replacing all of its windows, and she was [laugh]—she was sort of awestruck. But at these weekly meetings, in addition to learning about what’s going on with the city, and the history of the city, because the buildings, as you know, landmarks could be any age as long as they’re over thirty years old, and the range of projects. And also envisioning what the city will look like. So often, major projects, you’re seeing them five years before they’re executed, so it’s fascinating.

But for all of these applications, I was usually most involved by public testimony. And specifically, Ed Kirkland, who was, I guess, the Director of the Public Review Committee at the Historic Districts Council. He really testified on everything, whether it was on behalf of HDC, or personally. And he was so, you know, he was authoritative, charming, brilliant. And actually, for NYPAP, in an obit I wrote for Ed a couple of years ago, I cite him as the most important influence on me as a civic preservationist. And I still go to the hearings. I testified on behalf of the Art Deco Society on Tuesday about the Western Union Building. They didn’t do what I told them to do, but I was still there! Obviously, I’ve got stick-with-it-ness.

Q: Can you explain what you mean when you say civic preservationist?

Calderaro: Well, I suppose, I’m not a professional preservationist. I’m not a professional historian. But I am an engaged citizen who is passionate about the city, and preservation, and our built heritage.

Q: And that’s rooted in an understanding that this improves the life of the people.

Calderaro: Yes.

Q: That’s why you say civic.

Calderaro: Yes, absolutely. It’s all around us. It’s our built heritage. One of my current projects, for example—or hobby horses, as I like to say—is the demolition of historic buildings that are not designated by the Landmarks Commission, and they become vacant lots for years and years and years. In this very neighborhood, on 29th Street, the Bancroft Building was demolished eight years ago, in 2015, and it’s a vacant lot. It’s a vast, block-long vacant lot. And across the street is another one, and around the corner is another one, and the Kaskel Building, and the Demarest Building. I just saw another one today. I’m working with various organizations on that, trying to get some attention to that, and hopefully to engage the newly established Commissioner of the Public Realm because I think a person with a title like that should be interested in this. So I’m working through my channels to make a case for that.

Q: What is the Commissioner of the Public Realm?

Calderaro: I don’t know [both laugh]. It’s a new position established by Mayor Adams, and a lot of negative people—I’m not negative, by the way—but a lot of negative people say, “Oh, it’s just another Transportation Alternatives person.” Well, you know Transportation Alternatives, apart from the fact that I’m a bike rider, they are involved with pedestrianization and public spaces. [00:20:01] So trying to think creatively about solutions for a very urgent problem, most recently exacerbated by the demolition of the Hotel Pennsylvania, which was the largest hotel in the world when it was built in 1919, with two thousand rooms, and now it will be a vacant lot for the rest of my life, and perhaps even for the rest of your young life [laugh].

Q: Wow. So what is your recommendation instead of this? Is it to build something new, or is it to stop the demolition in the first place? How do you––

Calderaro: Well, stopping demolition in the first place is the place where it should be. There are different theories. Gale Brewer had this idea years ago that every building that was proposed for demolition, that’s over fifty years old, should be reviewed by the Landmarks Commission. But, the issue is that the Landmarks Commission did not designate the Hotel Pennsylvania, or any of the other buildings that I mentioned. So that’s not really a solution. Is the answer a demolition tax? Or is there—a lawyer from LPC, John Weiss, said a month ago, at a forum on 6th Street, “Well, we can’t make developers build buildings.” But something has to happen. So for example, on the Penn site, make it a park. Vornado and Steve Roth should be forced, somehow, to pay their penance. They say that the neighborhood was blighted. Well, sorry Steve, you created the blight. And how that happens, I don’t know, but at least I’m raising the issue anywhere I can, including here.

Q: Yes, absolutely. It sounds similar in some ways to a vacancy tax for landlords that keep rent stabilized or rent controlled apartments vacant on purpose, instead of renting them out. The crisis of housing is partially—you can see it visually.

Calderaro: Yes, exactly.

Q: It’s an issue of vacancy sometimes.

Calderaro: And the tragedy is that a building is gone and it’s forgotten, completely. I mean, I have to remind myself sometimes, “Wait, what was here?” I was riding my bike down 29th Street today and I said, “Oh, what was the name of that wonderful hotel that’s now been a vacant lot for a year?”

Q: Yes, and of course when they’re historic, it’s a loss of a whole other element, aside from just, simply, use.

Calderaro: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Q: Let’s talk about your involvement with Community Board 1.

Calderaro: Sure. I lived in Battery Park City, and being a joiner, I joined Community Board 1. My committees were the Battery Park City committee because I lived in Battery Park City, in a modern building, by the way. I have nothing against modern buildings, and there was nothing there, you know––nothing was destroyed for this modern building. And also the landmarks committee. So I was on the board for, I think four years. I’m not quite sure. Julie Menin was the chair. And as you know, on the community board, you’ve got monthly meetings. But then you’ve got regular committee meetings for Battery Park City, and also for the landmarks committee. And again, it was fascinating. It’s all Community Board 1, but there’s so much going on in lower Manhattan. It’s where New York began, so there’s so much history, it was such an education. It was everything from Chinatown to Tribeca, to also the World Trade Center site because this was when it was all being envisioned. It was nothing. It was a sixteen-acre pit at that point. So it was fascinating, very interesting. And I didn’t resign until I moved here in 2014.

Q: What was it like to live in Battery Park City?

Calderaro: It was lovely. I lived on the river, and in the first environmentally conscious high-rise residential building, which was built with liberty bonds, which was an incentive for people to build housing to get people to move to, or build, in lower Manhattan after 9/11, because nothing was certain. So it was affordable as well, and it was just beautiful. I mean, I remember walking out my front door and turning left, and Elton John is doing a concert—free—on the plaza. But it was just wonderful. [00:25:01]

Q: I mean, I was there maybe for the first time, I guess, not too long ago, and I was really struck by how much parkland there was, and just right beside some high rises that felt like you didn’t really realize you were in the city.

Calderaro: Yes.

Q: I was wondering how it felt to live there. If it felt like, as far as something that’s been recently designed in New York, relatively recently, did it feel like it functioned in the way that the planners had envisioned?

Calderaro: Well, it did really feel like an enclave, in that if you walked out my front door, you had Rockefeller Park, which is one of the gorgeous parks. And then my apartment overlooked Teardrop Park, which is designed by the wonderful Michael Van Valkenburgh. So now you’ve got probably more than a decade-old park. So this might have been where you went. The foliage is huge, and the trees are established, and it’s by Van Valkenburgh—he’s probably one of the most pre-eminent landscape architects in the country, if not the world. And he also did Brooklyn Bridge Park, for example, and other projects. It was quite idyllic. And then I would just ride my bike up to Columbia, where I work, up the bike path, every day. So I always said that I was much more in touch with nature than my friends who lived in the suburbs.

Q: Yes. I can see how that would be very true. So when you were living there, were you living there during 9/11?

Calderaro: No. I moved after, because the building wasn’t built. The building was a hole in the ground on 9/11. Then after 9/11 happened, they restructured the financing, and put in some affordable units through liberty bonds. I was there after, but, you know, 9/11, still, I think some parts of the city are still being rebuilt, like the church that just reopened about six months ago? Or the Perelman Art Center, which opened what, two weeks ago? So [laugh], so the recovery is still happening.

Q: So on the landmarks committee of CB1, what kind of things did you discuss?

Calderaro: It was usually what was coming up at the Landmarks Commission. So applicants are encouraged to go to the community board before they go for their hearing. And at every hearing, the chair or staff member reports on what the community board said. They don’t detail it, though. They say Community Board 1 recommends approval. Community Board 1 recommends disapproval. There’s no detail. That’s why I think it’s so important to be there, and have the commissioners hear your testimony. So basically, it was hearing what would be coming up at the LPC the following week, or the following month, or whenever, and it was, again, wide ranging. So for example, I mentioned Chinatown, Tribeca, but you also had Governor’s Island. So it was just really fascinating.

Q: Did you have a sense that the commissioners were interested in what the community boards were reporting?

Calderaro: I think so. They have input from the staff, obviously, and then they have input from organizations like the Art Deco Society, the Victorian Society, HDC. But the community board is the official voice of the public, and if they don’t have an interest in it, they should. Although again, they don’t go into any detail, so it’s not as nuanced as, let’s say, the Victorian Society testimony.

Q: Do you have a sense of there being, maybe, any kinds of shifts in the way that the commissioners consider the community board, or the community responses?

Calderaro: I really don’t. I mean, because they don’t show their hand. [00:29:53] With regard to that, we always were diligent, and operated on the assumption that our work, and our efforts, and our opinions held water, and were paid attention to. I can’t comment if they were or were not. But I mean, certainly everything is submitted, and they receive materials before the hearing. Did they read them? I don’t know.

Q: Do you recall anything that was either landmarked or historic districts that were designated while you were serving on that committee? In your district.

Calderaro: Yes, that was the other thing. We did comment on designations. I’m just trying to think if anything––mostly, they would have been individual buildings, not necessarily districts. Although I, among others, were and continue to lobby for a Little Syria district on Washington and Greenwich. It’s not going too far [laugh], but we’ll continue to try that. So that was something that I was personally involved with, and I know that the committee was advocating. But largely, we loaned our voice in support of most designations. And I’m just thinking about some of the big applications. So there was—is it 346 Broadway? The Clock Tower Building. It’s a massive building.

Q: Oh. 346.

Calderaro: Yes. It was being proposed––this is now years ago––but proposed for residential conversion from a city-owned government building. I forget what office. The courts, maybe, or something like that. This gorgeous massive block-long building. And it was a multi-faceted proposal because the building is so big. And I learned that there are five interior landmarks within the building. So that was very fascinating. And then the whole issue, which is still going on right now, I think––I know there was a decision––but about the space around the Clock Tower. Is it publicly accessible? Could it become a private apartment? I think it did. But that’s just one example of a complicated project.

Q: And where a Certificate of Appropriateness was issued against everyone’s advice or testimony.

Calderaro: Yes, that’s sounds right. It’s a beautiful building, though. Filled with movie stars, I think.

Q: We always like to consolidate all the important stuff in culture.

Calderaro: Right [laughs]. But the building looks much better than when it was owned by the courts or whoever it was. I wish there were a public function. And that’s another one of my issues/hobby horses. When the economic development corporation spends millions, or tens of millions, or however much they spend, to renovate an historic building. And then it becomes a private club, like the Battery Maritime Building, which is now literally, the Club Cipriani. It’s a private hotel, a members organization. They do do benefits, so if you want to spend a thousand dollars, you can have dinner there. And they also do art fairs. But that’s another, whatever, one hundred bucks for the day, or whatever it costs. So that’s unnerving when they get involved and spend public money to create it. And it’s not the first time that Ciprianis have come in and privatized magnificent public spaces—including 25 Broadway, and the building on 42nd Street, among others. And others would argue, it’s like, “Well, did you want the Battery Maritime Building to fall into the river?” “No. But does it have to be publicly subsidized to become a private club?”

Q: Right, which is really not about accessing the building. The civic element is kind of replaced with the capitalist element––“capitalist preservation,” I guess. So I wanted to ask about, to bring up Ed Kirkland again. And I think this is something that you’ve written about, in what you’ve written for NYPAP eulogizing him, about how he had lobbied for a zoning plans by residents. [00:35:03]. That’s the city’s first zoning plan led by residents. That was under his guidance in West Chelsea.

Calderaro: Yes.

Q: So I guess I wondered if there was anything that you had been involved with, with rezoning in Community Board 1.

Calderaro: There weren’t any big rezoning proposals that I recall at Community Board 1. I didn’t work with Ed on that proposal, I wasn’t in Chelsea then. I knew about it, and I cited it among his many accomplishments, but I really wasn’t involved with rezonings.

Q: Are there other examples of that?

Calderaro: Well, what’s happening—I’m not really comfortable talking about rezoning because I’m just not conversant enough and I don’t want to speculate about what’s going on.

Q: Well, maybe a more general question. Is there anything that you had a sense of that you kind of wished the Community Board could have more hand in, given that it is, as you said, the voice of the community? Just things that you imagined like, “I wished this would have worked differently.” Or, “I wished that this was something that we could take more of a lead in.”

Calderaro: Well, it wasn’t so much on the Landmarks Committee of Community Board 1, but in my other hat, as co-chair of the Battery Park City Committee. Because Battery Park City, as you probably know, is a state entity. It’s run by the Battery Park City Authority, and they control every aspect of it. And they really operate rather autonomously. They’re not part of the city, and they certainly don’t have any landmarks, and we said what we said, when we said it, about whatever it was, but I don’t think that sufficient attention was paid, and probably because they are a state entity that reports to the governor, not to the mayor. And also, everything at the Community Board is advisory. And that’s probably another point of contention, or an issue, that yes, we are the voice of the public, and yes, it’s completely advisory, and yes, it can be ignored.

And likewise, with city projects as well. So when we’re testifying about Central Park or any city properties, it’s advisory. An advisory report is followed. And I think that in some cases, the commission does not exercise the amount of authority it could potentially have, and say, “Oh well, we’ll send a report, and good luck.” I don’t even know what follow-up there is with park projects.

Q: Thank you for that example. I can see how that would be a unique situation. Okay, let’s talk about Tin Pan Alley!

Calderaro: Okay! [both laugh].

Q: So how did you become involved in this?

Calderaro: I became involved when I moved to this neighborhood, to East 28th Street in 2014, 2015. And being a joiner, and a preservationist, I joined a local group, the 29th Street Neighborhood Association, which is involved with quality of life issues in the area, basically from 23rd Street to 34th Street, from river to river. 29th Street is just a moniker, it goes way beyond. It will often be referred to, because of the name, as a block association, but it’s not.

One of the many projects they were involved with was—and I think at that point the Historic Districts Council was involved—was the expansion of the Madison Square North Historic District, which ends at 26th or 27th Street. But they wanted to expand it north, and east, and also west. And I had started to fall in love with the exuberant late 19th, early 20th century architecture in this area, namely these hotels that were built in service of what was then the cultural and entertainment center of New York City, particularly on lower Fifth Avenue. [00:40:05] Then theatres going up Broadway, and the original Madison Square Garden, which was on Madison Avenue and 26th Street. And I said, “This sounds great. I can get behind it, but what is this Tin Pan Alley thing?” I looked at a map, and they had just one little line on 28th Street, between Broadway and Sixth. And when I learned that it was the birthplace of American popular music, and that buildings were intact from the 1850s––and that it was invariably threatened, because there’s a lot of development and opportunity in the neighborhood––I got very passionate about it and coalesced a committee and a group. We organized, we reached out to elected officials, and developed goals, and enlisted a lot of support from everyone from preservation organizations, to music organizations like ASCAP, and also the descendants of the sheet music publishers, songwriters, and performers.

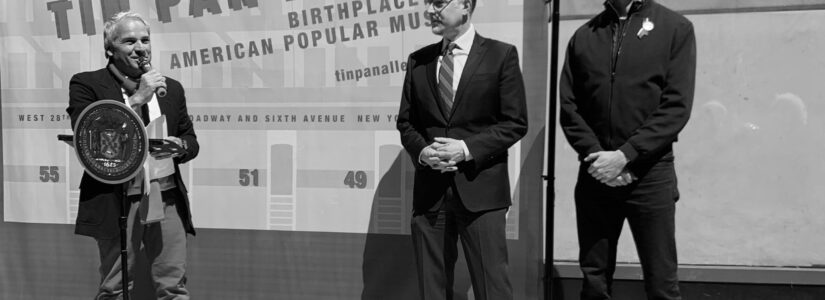

Then we also went to cultural organizations like Carnegie Hall, and the Museum of the City of New York, and basically, anyone who would support us. We developed a campaign, and we did a Tin Pan Alley Day in 2017 to call attention to the program. I reached out to our elected officials at that time. The city councilperson was Corey Johnson, whose chief of staff was Erik Bottcher, who’s now our city councilperson, and we worked side by side with him, the 29th Street Neighborhood Association, and the Historic Districts Council. And also historians like Andrew Dolkart at Columbia; John Reddick, the Harlem historian, who specializes in Black and Jewish music 1890 to 1930; David Freeland, who wrote the book, Automats, Taxi Dances, and Vaudeville, that concerns itself with the Tenderloin. And I know I’m glossing over a lot, and we can go back and look at some of it.

But basically, we went to the commission several times and they said, “No.” I should preface this by saying that before me, people had been going to the LPC for a designation of the birthplace of American popular music for decades, and being told no. And I was told no. People said, “You’ll never get anywhere!” And they’ll tell you that as well. But lo and behold—after not that many years––I moved here in 2015, so on December 10, 2019, the commission designated five buildings as Tin Pan Alley landmarks, 47–55 West 28th Street. These buildings are and are emblematic of the offices of sheet music publishers who descended on the area in the late 1890s. And by the turn of the century, there were dozens of sheet music publishers, accompanied by songwriters, and artists, and performers, who worked together for the first time, which is why they call it the birthplace of American popular music, because they created the sound, but they also created the modern music industry.

And now Tin Pan Alley is known worldwide, but a lot of people don’t know where it was, and where it started on 28th Street. I have people every day who say to me, “I know all about Tin Pan Alley, it’s the Brill Building.” And I say, “Well, no, that’s in the 50s on Broadway, and that was more in the 1950s with people like Carole King and Neil Sedaka, and the pop machine.” And they say, “Oh, I know all about Tin Pan Alley, it’s Denmark Street in London.” And I say, “No, that was a little bit later.” It does have music credentials, but it was probably more in the British Invasion and The Beatles. But it’s still going strong, and still identified with music. I think it’s a credit to Tin Pan Alley that the name is known worldwide, and we’re trying to let people know what the history is, and I think that’s what’s really key. It’s the Eastern European, Jewish songwriters like Irving Berlin and George Gershwin, and African Americans like J. Rosamond Johnson and James Weldon Johnson, and the influence of various communities to create the Great American Songbook. [00:45:06]

I always say that the way that Hollywood became synonymous with filmmaking, Tin Pan Alley is synonymous with songwriting. If you Google Tin Pan Alley, you will have six million matches. I have a Google alert. It’s fascinating to see what comes up and what people are calling Tin Pan Alley.

Q: I’m trying to figure out when I first started knowing those words.

Calderaro: No, it was all new to me because I approached it––people always say, “Oh, are you a musician?” And I go, “No, I approached it as a preservationist.” I might even say historian, but as a preservationist, and as a New Yorker. And it really seems to have captured the imagination of people. People said to me after the designation in 2019, “What are you going to do now?” And I say, we’ve been working on this for years, but we formed the Tin Pan Alley American Popular Music Project. We got 501c3 nonprofit status, and we’re doing events next week. I’ll give you the date for the record: Oct 13, 2023. We’re kicking off the Museum of the City of New York centennial weekend, recognizing the cultural history that the museum is trying to preserve, and Tin Pan Alley is very much part of it. We’ve done events at the Park Avenue Armory. We’re doing something in 2024 at Summer Stage. We’re doing tours next week as part of Open House New York. Just to give you an idea, last week we did a tour of the Music Hall of Fame at Woodlawn Cemetery, with the Tin Pan Alley personae who are permanently residents there.

Q: Where did the name Tin Pan Alley come from?

Calderaro: There are a few stories. The one most commonly told is that a journalist, Monroe Rosenfeld, was interviewing Harry Von Tilzer, who was one of the first publishers in Tin Pan Alley, and there was just a cacophony of noise from these tinny pianos, these upright pianos. It was people trying out their songs for sheet music publishers, for performers, for customers. So there’s this cacophony of noise, and Rosenfeld said, “How can you stand that noise?”—or that “tinny noise”—and von Tilzer responded, “Yes, it’s a regular Tin Pan Alley.” He was writing for The World, the newspaper and Rosenfeld said, “That’s what I’m going to call my article.” And the name stuck, which is incredible.

Q: I wanted to ask about the earlier efforts before you came along. I think when I had talked to Simeon, he had said that it was also Sarah Carroll, who was the director of preservation at the time, and they were walking around and there was just no cultivating an interest in her. But then at the same time, she was the head when it was approved. So he had expressed some frustration or confusion there, and I wonder if you had any sense of maybe what changed, that suddenly made it—

Calderaro: I’m not sure if it was Sarah Carroll, or was it the commissioner at the time, Jennifer Raab, who was the predecessor?

Q: Who was walking around with Simeon?

Calderaro: I could be mixing it up with the Meatpacking District, which I was also involved with, which Jennifer did say, “I don’t see it.” In any case, I’m not sure if there was a change with Sarah. We had been lobbying Sarah, but it also could be the director of research as well, who’s currently Kate Lemos McHale. And it was funny, in one of the meetings I had with Kate and John Reddick, and David Freeland and Andrew Dolkart, I was able to hand a Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation [GSAPP] paper to Kate, where they recommended Historic District designation of Tin Pan Alley, and Kate was one of the authors. [00:50:07]. So it could very well be—I don’t even know if she remembered that. But anyway, that could be a key.

But then also it was the moment. Tin Pan Alley was not designated as an architectural landmark. The buildings are nice, and they’re intact; they’re 1850s Italianate row houses, which were built for the middle class in the mid-19th century. And then it became offices, and the middle class and the elite moved further north. But it was designated, obviously, because of the cultural significance—specifically, of the music industry, and the early music industry. And it’s also that they were intact. You know, quite frankly, the whole area, as I said earlier, it was the entertainment and cultural nexus of New York City in the late 19th and early 20th century, which was a very architecturally exuberant period, as you can see evidenced right now. But to a certain extent, these buildings were selected, and as you probably know, and anyone can look, they were filled with sheet music publishers. And the commission, among others, have done great research on each building, what publishers were in each building. So they’re undeniably significant. But any number of other buildings in the area—on 28th Street, on 29th Street—could have been designated. At 40 West 28th Street, Albert Von Tilzer, Harry’s brother, wrote Take Me Out to the Ballgame, even though he had never been to a ballgame. [laugh]

Q: How did you get connected with John Reddick?

Calderaro: I became connected first with John Reddick when I worked at the Studio Museum in Harlem because, as I said, he’s a Harlem historian, and we’ve been connected ever since. But since his area of expertise is Black and Jewish musicians, 1890 to 1930, that he was a perfect partner. But it’s interesting, even before any of this got started, my day job at Columbia is in community relations. John is a [Columbia] Community Scholar, and I presented him as the first Community Scholars Lecturer in 2016, where he talked about this very topic. And then we’ve gotten closer and closer. We’re working together on a program in the spring, to inaugurate the Bronx Music Hall about the Harlem Hellfighters, and James Reese Europe, and the program there. He’s on our board now, and on various committees. We were just meeting yesterday to talk about Summer Stage, because that’s going to be offered in Harlem, in Marcus Garvey Park, on August 16, 2024. And I saw him last night at a GSAPP event, too.

Q: Sounds like a very popular event! [both laugh] Did you have a sense, when you were gathering people together and, you know, bringing different kind of experts and parts of the community into this conversation, that it might just work this time? That it might just get the designation?

Calderaro: I don’t even know that I thought about that. The councilmember, who I mentioned, Erik Bottcher, has referred to me publicly as “a dog with a bone.” I believed in it so much, and the merit, and just pursued it, whether it got designated or not. Not that I didn’t care. But calling attention to it into the campaign was my priority, so I was delightfully surprised when it was designated. And it still took effort––the owner opposed. As you probably know, owners often oppose landmark designation, and was rather scurrilous in his opposition and saying, “Well, look at the stereotypical depictions of African Americans,” and “How can you say that this is a landmark?” [00:55:01] And we had a number of African Americans, including the descendants of the composers, and people like Mercedes Ellington, the daughter of Duke Ellington, and historians and community activists, like Claudette Brady in Bed-Stuy, among many other people, who just shot down that argument. So happily it went by the wayside, and now he no longer owns it. I think he didn’t pay his debts and Wells Fargo took over the building. So we’ll see. That’s also on my list, to reach out to the bank and say, “What’s going on with these buildings?” Because it was also an example of preservation by neglect. The buildings were intact because nothing was done with them. Nothing still has been done with them, so it’s a real opportunity. But there are things that are catching on. The Ritz-Carlton just opened up where we’ve done programming with them, and they’re on 28th Street on Tin Pan Alley––they have a Tin Pan Alley cocktail. And also we’ve done performances with them on the plaza. There’s another hotel that’s opened, the Fifth Avenue Hotel, and they’re very aware of the history. Smart business people know the value of their history and their location. And in fact, there’s a new restaurant-bar called Tin Pan Alley on 29th Street.

Q: With a lot of efforts to get areas or individual landmarks designated, it seems like there needs to be some sort of level of buy-in from community members. You talked about the community board as being one of those kind of representatives of the community. Who were the players, besides the 29th Street Neighborhood Association, that were maybe part of bringing some energy to this public education about it?

Calderaro: I really have to credit Save Chelsea, and Lesley Doyel and Laurence Frommer, among others, who were spearheading the campaign before, the Save Tin Pan Alley Committee, and then eventually, the Tin Pan Alley American Popular Music Project. So I think they were the driving force and our partners, and we worked with them on our various events. And then the community board, they didn’t necessarily oppose the designation, but they weren’t particularly aggressive in the designation––and they generally aren’t––I don’t know whether they see that not as their role to be community advocates for designations. But then also, of course, HDC. I think they made us one of their Six to Celebrate, tthat campaign they have to call attention to meritorious potential landmarks.

Q: What sort of interactions did you have with the business improvement district [BID] in the area?

Calderaro: It’s now called the Flatiron NoMad Partnership. It was previously 23rd Street Partnership, the BID. And we included them in our discussions, and we appealed to them, but it was really after the designations that we became actively involved with them, with one major exception––no, it was actually after the designation. It was in 2021 we worked with the Flatiron NoMad Partnership in presenting Tin Pan Alley Day. It was after COVID, September 2021. So we were thinking we might be through the first wave of COVID. So we organized a public celebration: five hours with fifty performers, for 5,000 people on the Flatiron Plaza between Eataly, right at the intersection of Broadway, Fifth, and 23rd Street. And they were wonderful partners. They gave us the space, they arranged for the street permit, they gave us a couple of dollars. [01:00:01] They were really great partners in that.

And then subsequently, they were doing a rebranding, and they put up signage on 28th Street saying Tin Pan Alley, between Broadway and 28th. And that’s because we don’t own any of the buildings. It’s really awareness through digital media and some signage. And then also, they were with us for the celebration of the co-naming of 28th Street, between Broadway and Sixth Avenue, as Tin Pan Alley, and that was in April 2022, I think. They were great partners, and they splash us all over their material, which is great. We welcome it, because again, a lot of what we’re doing is about awareness.

Q: Is there anything else about this process that you want to bring up?

Calderaro: Let me see [reviews notes]. Apart from what we are doing now, I think that the momentum is just getting stronger. Now people are coming to us and saying, “What can we do? We want to have an event.” The Madison Square Park Conservancy said, “Can you provide entertainment for our Christmas tree lighting?” Which is the oldest Christmas tree lighting in America. You know, it’s perfect. It’s a great situation to be in. As I mentioned, the Museum of the City of New York, all of these really prestigious organizations are working with us, large and small.

And also, because we don’t have building, we don’t have any borders. So we did a great event this summer at the Alice Austen House, because that’s very much in our period. Alice was late 19th, early 20th century. I was speaking with someone at the Lambs Club, which is the oldest theatrical club in America, and we were talking about doing a program on Long Island, of all places, and now the Bronx. So we’re spreading the word in our digital media. We have a board—bless them—of twelve members, and we just had our first strategic planning retreats. So we’re envisioning the organization and what we want to do. But in the meantime, we’ve got a lot of activity, a lot of concerts, a lot of lectures, and then also collaborations and partnerships.

My one specific goal is, as I said, place-making. Cultural place-making, whether that’s digital or it’s physical. Signage and awareness is really, I think, what our mission is. And bringing together, and sharing the history, but also the cultural history, the Eastern European, the Jewish, the immigrant history that’s embodied in Tin Pan Alley. And that’s a universal, evergreen, for-all-time story that needs to be shared, especially now, with what’s going on with the current immigrant history that’s being created.

Q: Yes. I think this might have been at the naming ceremony––I watched a video of an event, and I think John Reddick had kind of described Tin Pan Alley as a story that is about two outsider groups coming together, Black people and Jewish people. And I’m wondering, is that a narrative that’s unfolding in some of the programming that you’re developing or events?

Calderaro: Oh, absolutely. It’s embedded in it. And none of our programming is exclusively African American, or exclusively Jewish. It’s certainly part of what we’re doing. In fact, we have done programming––we’re talking to Save Harlem Now! and we’ve also done programming with the Manhattan Jewish History Initiative. We spoke at and provided performers for their 2023 Jewish Hall of Fame induction ceremony, and now we’re talking to them about an event at Temple Beit Simchat Torah on 30th street. It’s here, it’s the gay temple, and it’s right on 29th Street. [01:05:01]. We were talking to them about a concert, an event, to tie together the history of the neighborhood, and the Jewish history, and probably the gay history, all right here. So bringing in various affinity groups, another great opportunity.

Q: Wow. Are we in the HQ of the Popular Music Project right now?

Calderaro: Yes [both laugh]. It operates out of my apartment, which is fine. Because again—and I probably will always regret saying this—we don’t own the buildings, we don’t want to own the buildings. But that’s a different scale. Then you become involved with cafés, and HVAC, and shops. And right now, one our initiatives, a big goal, speaking of the hotels, is to train tour guides. Since we don’t have a headquarters, we want to be able to bring people in and interpret it not for us, but with us. I was just speaking with someone last night, a tour guide, and I invited her to come to a tour we’re doing as part of Open House New York next week and see what we’re doing. And there’s also a virtual tour online as well. And then Tin Pan Alley can be a gateway to the whole area, whether you’re talking about Madison Square Park, or the Fifth Avenue Hotel or the whole history. Or vice versa––this can be a gateway to Tin Pan Alley. Because the neighborhood is growing, and it’s very vibrant.

Q: I actually work sometimes on 26th between Sixth and Seventh, and I think I just went to go get some coffee one day, and I was like “Oh! I’m here.” [both laugh] There is such an intersection of tourists and people who work nearby, and of course, people who live here, because there’s so many residential buildings. And it really is just a—as far as landmarks in the city—just more a mix of use in more ways than some of the other iconic buildings. And it’s so accessible, geographically, as well as accessible to so many different elements of cultural history.

Calderaro: And you look at some of the great—well, the Flatiron Building alone is a signature landmark. And then you look at others that are not designated, and not necessarily historic architecture, but the Flower District, right there on 28th between Sixth and Seventh. It’s diminished, but it’s still a vibrant place, especially early in the morning when all of the florists are picking up their flowers. And that has a connection to Tin Pan Alley in that it likewise was created by immigrants, and also, it was created in service of the entertainment cultural center. So the flowers were going to the theaters. They were going to Madison Square Garden, they were going to the stars in the theatre, they were going to the whorehouses in the Tenderloin, and the sporting clubs. And all of these places, in addition to having flowers, they all had pianos. Because as you know, there was no radio, there was no phonograph in the late 19th century. So the coin of the realm, or the name of the game, was sheet music.

I went to a lecture at the CUNY Graduate Center, and it was called, “How Did New York Become the Cultural Center of America?”––or “the World?” And various people were talking for a couple of hours, and one man in frustration said, “Okay, we’ve been listening to you for two hours, but pinpoint it. How did New York become the cultural center of America?” Because there were various tangents and different speakers talking about their themes. And one professor said, “Alright.” It goes down to printing, both of them. One was the newspapers, you probably know. I mean there were what, eighteen daily newspapers in New York City, each with four editions going around the city, going around the world. And I don’t even know if that number would include the international, the foreign language newspapers. So word was spreading all over, certainly, the region. And he said that the other printed matter that spread American culture across the world was Tin Pan Alley, was the sheet music.

J. Rosamond Johnson and his brother, James, tell the story of they were getting on a ship to go to London. And when they were leaving, they said they were played off by a band—cause there were bands everywhere—to Under the Bamboo Tree [01:10:08]. It was one of their songs. And that was wonderful. And they landed in London and they were greeted by Under the Bamboo Tree [laughs]. So the word was spreading, and the music was spreading, and it still is to this day in popular music, which is, you know, global—because of Tin Pan Alley, maybe. [laugh]

Q: I mean, all roads lead to Tin Pan Alley––I’m going to walk out of here and think that [both laugh]. So I want to ask you about, I guess, as a communications professional, how do you think about, or what advice do you have about thinking about these efforts to designate or landmark places as campaigns, as information for the public—not just for the Landmarks Preservation Commission?

Calderaro: Well, I think they go hand in hand. Because what Sarah, and anyone who’s ever worked with the Landmarks Commission will say, is you need community support. It’s very political. You need to show the Commission, but also the local elected officials, and the community boards, that you have support. So I think that communications and awareness is key, and essential. Unless there’s something that’s undeniable, and the Commission can turn around and designate on its own. For example, there was a building on Madison Avenue, and the lobby, just out of the blue—it’s a Warren & Wetmore lobby, right over here on 30th Street or something [between East 35th and 36th Streets]. I didn’t know anything about it, no one knew anything about it. Where did this come from? And there was no campaign that was necessary because the building owner was in support. So if you’ve got the building owner who is in support, who is potentially the one that’s going to derail the designation, then that makes things easier. But in most other cases, you need to build community awareness, and support, and it starts with communication. And I know, certainly, with Tin Pan Alley, people are being educated every day. Everyone—everyone—a lot of people say, “Oh, I know the term Tin Pan Alley, but where did it come from? What does it mean? Where is it?” And that’s what our job is, to tell them.

Q: Did you know from the get-go that you would want to continue working on this? Like the outreach part, the programming part?

Calderaro: No, it’s happened quite organically, and in a really beautiful way. I mean, I talk about Tin Pan Alley day and night. But things come to fruition through persistence. And also because it’s a great story. It’s a great American story. It’s a great New York story. I know with the Museum of the City of New York, I’ve been lobbying them for five years, and with Summer Stage as well. And everyone thinks it’s a great idea, but how does it happen? So now, currently, I’m reaching out, as part of the 60th anniversary of the Landmarks Law, to the Society of Illustrators, for example. Ideally, perhaps, presenting an exhibition of sheet music, which are artworks in and of themselves, because the sheet music, it was a marketing tool. So you had the beautiful Gibson girls, or the bands, or this beautiful sheet music. So that’s another angle to interpret and tell the story.

Q: Like you said, it’s such a good story––not only that, there are so many different elements to it. And this is something that’s especially exciting for cultural landmarks, is that it isn’t just the architecture or the use, it’s also images, sound, a bonanza of different avenues to get people interested, and to plan out the next twenty years of what you’re going to do with your evenings and weekends!

Calderaro: Exactly. And what we’re really fortunate in this moment and time is that—I mentioned cultural place-making—is that Tin Pan Alley is history in the very place where it occurred. So for example, I have in my vision, a multi-year grant from the Mellon Foundation, which has a Humanities in Place program. [01:15:04] And often that will take the shape of, let’s say, a southern plantation, or some very unsavory history, documenting what took place. But here it’s a beautiful story, and it’s here, and the vestiges are still here, and the buildings are still here. So again, cultural place-making I would put close to the top of our goals in sharing the history.

Q: Well, I just went to a Meet the Funders event with them, and I believe the quote was to make sure that your application and your proposal to them is “singing with humanities.”

Calderaro: [laughs] Oh my goodness! Oh thank you, I wish I had known about that. I’m circling around them.

Q: Is there anything else that you want to bring up in this chapter of your history?

Calderaro: I think we’ve covered a lot.

Q: And I hope there’s another opportunity for us to talk about the Upper East Side, Victorian Society, all the other––HDC in detail.

Calderaro: Art Deco.

Q: Art Deco. Yes, exactly.

Calderaro: I look forward to it. Thank you very much.

Q: Thank you so much.