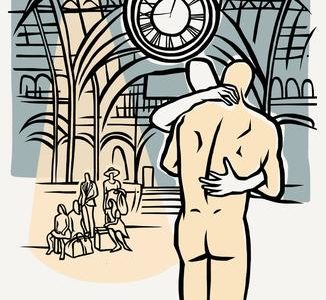

Love & Preservation, Perfectly Entwined: Pennsylvania Station by Patrick E. Horrigan

February 5, 2019 | Matthew Owen Coody, Archive Project Board Member

Like the tale of McKim, Mead & White’s legendary station itself, Patrick E. Horrigan’s new novel Pennsylvania Station is a bruising story of heartache and transformation. Set primarily in New York City between 1962 and 1965, the building’s slow demolition over the course of those years is woven throughout the narrative and deftly parallels the dismantling of Frederick Bailey, the novel’s protagonist. Change comes for Frederick, but as with the changes wrought with the eventual passage of New York City’s Landmarks Law, it is too late to reverse some great losses.

A private, strait-laced architect, Frederick is mired in tradition (think a penchant for baroque music and Walt Whitman). As a middle-aged, closeted gay man, however, this charming traditionalism begins to veer towards pre-Stonewall era repression. But when Frederick meets the much-younger, impetuous Curt (via a bit of impromptu cruising in the Theater District during intermission at My Fair Lady, naturally), he becomes enmeshed in a conflicted relationship that tests his traditional notions. Curt’s youthful passion also draws Frederick into the activist movements springing forth during these years of change, including the nascent gay rights movement and the emerging historic preservation movement.

The reader might think that the theme of old guard meeting new sounds familiar, but the novel does not prove to be so tidily categorized and it is the more powerful for it. Horrigan’s characters are far from two-dimensional, and the situations, conversations, and thought processes are realistic and ring true. Horrigan also paints a fascinating portrait of mid-20th-century New York City, filled with delightfully obscure details and settings that breathe life into the narrative.

As the novel’s title suggests, Pennsylvania Station features heavily as one of these settings, the process of its demolition providing a symbolic parallel to key moments in the narrative, as well as providing touchstones in Frederick’s evolution both personally and as a budding preservationist. Anachronistically, despite being attuned to art, architecture, and beauty, Frederick is initially a reluctant participant in the movement that is emerging around him to protect historic structures. When we are introduced to Frederick he does not “believe in causes” and refers to the now-legendary rally staged by the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York (AGBANY) to protest the demolition of Pennsylvania Station as a “nuisance.” In a somewhat unexpected opinion for an architect, Frederick also describes Pennsylvania Station as a “sooty, baggy, ill-kept monster of a building, a confusing mix of styles—faux classicism, Crystal Palace ostentation… McKim, Mead, White at their excessive, pretentious, derivative worst…”. As one might expect, his viewpoint changes.

Many readers know that the demolition of Pennsylvania Station was not the sole crux of the preservation movement, and Horrigan also mentions other key losses such as the Brokaw Mansions on Fifth Avenue and the Rhinelander Houses in Greenwich Village. Their appearance in the text will give a thrill to any New York City preservationist, a refreshing feeling as the field has such minimal representation in popular culture. Some of these locations push Frederick on his journey towards a stronger preservationist mentality. For example, Frederick initially questions the significance of the Rhinelander Houses. Frederick ponders: “What, really, was their historical importance? Just the dwellings of another wealthy New York family…if George Washington never slept there, what was the point of saving the building?” But reflecting later upon the apartment building that replaced the houses, he bemoans “another bland apartment tower, another historic building razed to dust, a lazy design solution to appease everyone but please no one…great nineteenth-century architecture had been sacrificed for mediocre modern architecture.”

Some locations have a history of preservation activism that is lesser known, making their inclusion in the narrative feel like a subtle nod to anyone with a deeper knowledge of the field. The Mark Hellinger Theater, for example, where Frederick meets Curt during My Fair Lady, was one of the first theaters to be designated a New York City landmark after the demolition of the Morosco and Helen Hayes theaters in the early 1980s over the objections of preservationists. The Statler Hotel, more commonly known as the Hotel Pennsylvania, serves as the physical embodiment of a passionate night with Frederick’s former lover. Although the famed hotel has been threatened with redevelopment proposals since 1997, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission has denied activists’ calls for designation.

In addition to buildings, key figures involved in the early preservation movement make cameos throughout. Writer and critic Ada Louise Huxtable’s now-famous editorial on the demolition of Pennsylvania Station becomes a dramatic turning point for Frederick. Architect Philip Johnson’s personal life is cattily skewered in a conversation overheard during the AGBANY rally. Frederick also volunteers to draft entries on buildings for Alan Burnham’s book New York Landmarks. Horrigan also namedrops Harmon Goldstone, Alan Burnham, Lewis Mumford, Norval White, Mayor Robert Wagner, and, of course, Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses. Organizations and institutions are not left out either, from the activism of the Municipal Art Society of New York to the newly-founded historic preservation program at Columbia University.

Many of these key figures, places, and organizations are featured in the Preservation History Database on the New York Preservation Archive Project’s website. It is not a surprise, in fact, that Patrick Horrigan gives thanks in his afterword to the organization’s founder Anthony C. Wood and his book Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks, which helped him understand the history of the preservation movement and the role that Pennsylvania Station played in it. Horrigan also gained access to the Archive Project’s collections to view rare documents from the early 1960s, research that shines through in his writing.

Overall, Pennsylvania Station is a well-crafted, emotional novel that depicts the complicated, and often melancholy, inner landscape of a closeted gay man in the 1960s. The “tearing down” of these confines and the introduction of a bold new world is expertly paralleled with the changing architectural character of New York City at the time, subtly underlining architecture’s larger reflection of society as a whole. In fact, architecture and persona become inextricably intertwined. We know all too well what replaced Pennsylvania Station. But as the mighty edifice crumbles, and Frederick along with it, we are left to hope, perhaps naively, that his reconstruction will lead to something more beautiful.