In Memoriam

May 21, 2015

Article from the Spring 2015 Newsletter

Teri Slater, preservationist and co-founder of the Defenders of the Historic Upper East Side, died January 13th, 2015 at the age of 70. Born and raised on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, Slater was deeply passionate about preserving the character of this neighborhood and New York City as a whole. She was both an officer and a director of the Historic Districts Council, the citywide advocate for historic neighborhoods, and served alongside many community preservation groups in various efforts to protect the historic architecture of the Upper East Side. Slater was also a member of Community Board 8, sitting on its Landmarks Committee and co-chairing its Zoning and Development Committee.

Slater co-founded the Defenders of the Historic Upper East Side in 2003 with Elizabeth Ashby, another neighborhood preservationist whom she met in the early 1980s. This advocacy group is dedicated to protecting and preserving the historic character of the Upper East Side, which includes several historic districts and numerous individual landmarks. An ardent guardian of her historic neighborhood, she stated: “We love it the way it is, and we will fight to protect it.” Since its founding, the Defenders of the Historic Upper East Side has been involved with the creation of the Park Avenue Historic District (designated in 2014), blocking the construction of inappropriately-scaled towers in the neighborhood, and preventing the creation of a 3,000-seat performance space on Park Avenue.

One of Slater’s most well-known preservation battles was the opposition to the 2007 redevelopment plans for 980 Madison Avenue (located within the Upper East Side Historic District), which included a 30-story tower designed by prominent architect Norman Foster. The Defenders of the Historic Upper East Side opposed this idea and urged the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) to reject the plan, citing that the new tower would obstruct views throughout the Upper East Side and reduce the visibility of the iconic Carlyle Hotel. Due in part to her efforts, the LPC deemed this redevelopment plan inappropriate in January 2008, prompting a revised plan. The site has yet to be redeveloped.

In one of their most extended preservation initiatives, the Defenders of the Historic Upper East Side joined forces with Carnegie Hill Neighbors, Historic Park Avenue, and FRIENDS of the Upper East Side Historic Districts to advocate for the designation of the entire length of Park Avenue, from East 62nd to 96th Streets, as an historic district. Although some of the avenue was protected within the Upper East Side and Carnegie Hill Historic Districts, large swathes remained unprotected. The push for an historic district was in response to several architectural losses in these undesignated sections, and was intended, in part, to combat numerous development plans that could have caused further destruction to the area’s historic fabric. After a fierce battle, the Park Avenue Historic District was finally designated in 2014.

Slater also spearheaded less expansive campaigns. In 2012, Slater also began protesting oversized and excessive signage for commercial properties, especially along East 86th Street. Slater called for a replacement of the “gaudy” signs and storefronts with more modest signage, and encouraged enforcement of the installation of signs that comply with size regulations. Indeed, even up to the end, Teri Slater was still fighting on numerous fronts to maintain the sense of place of the Upper East Side. Community Board 8 Chair Jim Clynes called Slater an unparalleled resource in the community. “Teri’s knowledge of zoning and historic preservation was encyclopedic and her institutional knowledge of the city, the Upper East Side and the community board was historic,” said Clynes. “She will be sorely missed. She was indeed the ultimate defender of the historic Upper East Side.”

Daniel B. Meltzer, playwright, short-story author, and preservationist best known for his effort to preserve the interiors of the Upper West Side’s Beacon Theater, died November 6, 2014. He was 74 years old.

Meltzer was born and raised in Brooklyn, but by 1968 he was a resident of the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Meltzer’s father once owned and operated a movie theater, so it is not surprising that he spearheaded the preservation of the historic Beacon Theatre. The Beacon Theatre opened in 1929 as a moving picture and vaudeville “palace,” and continued to show films until the early 1970s, when live performances began. The theatre’s interior spaces were designated a New York City Interior Landmark in 1979. But by the early 1980s, the Beacon Theatre had become run-down, and Olivier Coquelin, a prominent developer of discotheques, announced his plan to gut portions of the theatre and turn it into a dance club. In response to these plans, Meltzer helped form the group Save the Beacon Theatre in 1985. As chairman, Meltzer led hundreds of volunteers in the fight against the proposed plan. They built a wide range of support, enlisting the help of celebrities such as Brooke Astor, Marvin Hamlisch, Yoko Ono, Harry Belafonte, and Judy Collins, while also recruiting over 20,000 people to sign a petition to save the theatre and leading demonstrations to advocate for its preservation.

Although the disco plan was unexpectedly approved by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, Meltzer and his group eventually had the Commission’s decision overturned in 1987, with the court ruling that the renovation planned by Coquelin would violate the building’s interior landmark status. This decision effectively saved the theatre. Subsequently the theater underwent a revival in its concert hall business, filling the void in New York City between larger venues and various smaller clubs. The Madison Square Garden Company eventually bought the theater in 2006. By 2008, they hired the architecture firm of Beyer Blinder Belle to begin a restoration which lasted over seven months, restoring the interior of the Beacon Theatre to its original splendor. Since its restoration the theatre has continued as a popular venue for a wide variety of events, including live music concerts by the likes of Bob Dylan, the Beach Boys, and the Allman Brothers, as well as the location for the Tony Awards and appearances by notable figures such as the Dalai Lama.

Judith Edelman, a “firebrand” in the architecture field, best known in preservation circles for her efforts to restore St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, died on October 4, 2014, at the age of 91. At the time of her death, she was still active at Edelman, Sultan, Knox & Wood/Architects (ESKW/A).

Edelman (née Hochberg) was born in Brooklyn to immigrant parents from Eastern Europe. She experienced an early childhood fascination with architecture, and decided to pursue the field after visiting an architecture firm when she was a junior in high school. Her interest in becoming an architect was further solidified when an injury prevented her from pursuing her first passion, dancing.

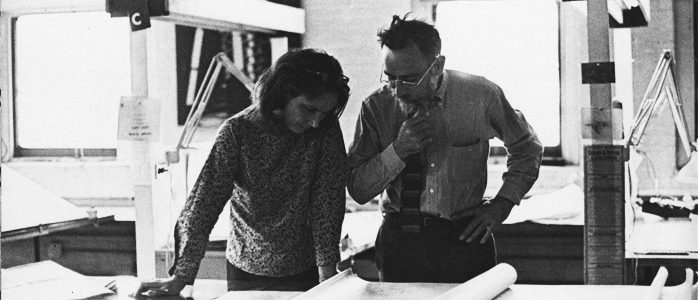

Edelman attended Connecticut College and then New York University before receiving her degree in architecture from Columbia University. After marrying Harold Edelman in 1947, she and her husband founded the architecture firm that is today called Edelman, Sultan, Knox & Wood/Architects in 1948. During the 1970s, she was a leader in the movement to include more women in the architecture profession, becoming the first woman to be elected to the executive committee of the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1971; by 1972, she also helped found the Alliance of Women in Architecture.

The Edelmans’ architecture firm did much to assist with historic preservation, including restoring the La MaMa Theater on the Lower East Side and the preservation and combination of nine brownstones within the Upper West Side Urban Renewal Area to create a unified multi-unit residence building (where Jackie Robinson was one of the first tenants). Judith Edelman’s most significant preservation triumph was when the predecessor of her present firm of ESKW/A, The Edelman Partnership, along with her husband Harold as lead architect, dedicated over three decades to the preservation of St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery. The effort began with the reclamation of the church’s historic graveyards. Then, in 1978, following a fire, The Edelman Partnership took on the renovation of the church, which dates from 1799, and the adjacent 1901 Ernest Flagg Rectory (now home to the Neighborhood Preservation Center). The project was finally finished 1986.

In this effort to restore St. Mark’s, Judith Edelman and her husband embraced a pioneering urban preservation approach in which young people gathered for hands-on assistance, an initiative called the Preservation Youth Project. In addition, under the Edelmans’ oversight and the supervision of a master mason and master carpenter, artisans performed most of the day-to-day restoration work. Harold Edelman, who served on the Board of the St. Mark’s Historic Landmark Fund, died in 1999. Judith Edelman remained a devoted and beloved friend of St. Mark’s until her death last year.