Fred Papert

The politics of preservation, deciding which battles to fight, knowing the politicians, makes all the difference when trying to save important historic sites as Fred Papert demonstrates in this panel discussion.

This is a transcript of a forum in the “Sages and Stages” speaker series that the New York Preservation Archive Project hosted in 2004. The featured speaker is Fred Papert, a former advertising executive who became involved in preservation in his own neighborhood, joined the Municipal Art Society, and then founded the 42nd Street Partnership in 1976. Papert discusses the publicity campaign that preservationists mounted as they fought court battles over Grand Central Terminal in the 1970s, focusing in particular on the involvement of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. He also recounts anecdotes from his career at the 42nd Street Partnership and addresses more recent debates over a new building in Carnegie Hill and the redevelopment of the far West Side. Throughout the interview, Papert gives his perspective on the politics of preservation, urging preservationists to choose their battles wisely, not to be afraid to compromise when necessary to achieve larger ends, and to hire good lawyers.

Q1: I want to welcome everyone to the last in this series of Preservation’s Sages and Stages, and thank our funders, which are the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the New York State Council on the Arts, who helped us pioneer and fund this program format—which, as many of you who have been here before know—involves a conversation style of both taping it for our archives, as well as, hopefully, leading to exciting conversation that will go with people beyond this room.

For those of you who have been here before, you know that the [New York Preservation] Archive Project was created to document, preserve and celebrate the history of the preservation movement, with the notion that if preservationists, as they do their work now and in the future, have a historical context within which to put their work—and realize that they’re not the first one trying to save a church; they’re not the first one trying to get a political body to approve the landmark designation of a site—but actually have some sense of how we tried to do that in the past, how it succeeded and how it failed, hopefully from that experience they’ll have a better chance of doing it in the future; or, at least they’ll consciously be able to think about strategy.

Today we have a real treat, because the topic is politics. One of the perhaps hidden secrets of historic preservation is that it doesn’t matter about your paint analysis, it doesn’t matter about the research on the building, but if you don’t understand the politics it doesn’t matter how good all the research is, you’ll never get the building saved. Politics is where it’s at, and we have with us today, as our sage, someone who has—if you’ll pardon the analogy—he has been the Yoda of the preservation movement when it comes to political strategy [unclear]. And if he is the Yoda, that would mean that Ken Lustbader is one of our jedi knights of preservation, in the field. And to formally introduce them, must then be Princess Leia [laughter]. She will formally introduce our speakers, and start the program. Thank everybody for coming, and now for the program.

Q2: Thank you. What a great way to launch the session.

Welcome to everybody. I wanted to spend a couple of minutes—you have a bio of Mr. [Fred] Papert and Ken Lustbader in your hand. You don’t have to actually read it too closely, but just some of the highlights of their biographies and why we have them here today. Fred is a former advertising executive and owner of an ad firm, who then got into preservation and became president of the Municipal Art Society [MAS].

Papert: A president who has a sieve for a brain.

Q2: He was at one point the president of the Municipal Art Society.

Papert: 1975 to 1976.

Q2: A lot of the preservation work he has done has involved, as Tony put it, an essential ingredient of preservation, which is the ability to influence the decision makers. We know, in looking at some of Fred’s work—the Grand Central Terminal fight, the fight over St. Bartholomew’s [Episcopal] Church, Lever House, his work on West Forty-Second Street, about all of which you’re going to hear stories from Fred—there’s always this real deft application of two different kinds of strategies. One strategy is about public outreach and the public campaign in getting people involved and getting press and publicity, but the other strategy is a very sly, behind-the-scenes ability to pick up the phone and call an influential person or a decision maker. One of the things we’re going to get into today, in addition to hearing some of the stories that Fred has to share with us—which are wonderful stories—is how do you decide which of these strategies to employ, which have been most effective, how do we apply them today, and in what sense are we successful in their application.

Ken Lustbader is going to interview Fred, and Ken has a master’s degree in preservation from Columbia [University]. He has been working in the field for over ten years. He’s a former director of the Sacred Sites Program at the New York Landmarks Conservancy, and is currently a preservation consultant. His chief client at the moment is a consortium of preservation groups that include the Municipal Art Society; the Landmarks Conservancy; the Preservation League of New York State; the National Trust for Historic Preservation; the World Monuments Fund. His consultancy is focused on preservation in Lower Manhattan, in the wake of September 11 [attacks], and so Ken is finding himself pretty much up to his eyeballs in the issue of politics, and in the dissemination of strategies and tactics and their application.

So in today’s session we hope to hear some stories, catalogue them and document them, but also to delve into this issue of strategies. Fred also, you will find, has a perspective on preservation that’s a little different than you’ve heard in the preceding three sessions, and I think we’re going to exploit that to the fullest, get your thoughts and your advice, and your insights.

So I’m going to turn the program over to Ken.

Q3: Thank you. Thank you. It’s interesting, coming from the Sacred Sites program, dealing with religious properties, and now dealing with politics—the two issues that no one is ever supposed to talk about at dinner parties. So here we are, talking about politics, and I’m sure there will be some religious overtones here, with Mr. Papert talking about St. Bartholomew’s Church and the battle to preserve that. But I think, in discussing this panel beforehand with Vicki [Weiner], we felt it was more important to hear about the stories. Then I’ll pose questions, specifically, about certain strategies that came up during the Grand Central battle, the St. Bart’s battle, the Carnegie Hill work that you’ve done—perhaps pre-charter reform and post-charter reform, and how that’s changed.

So, really, without belaboring my introduction, I think I’ll turn it over to Fred to talk about, specifically, what we’d like to hear. A lot of the people in the room here don’t know about Grand Central Station and what it was like—how that started; the preservation issues there; what your tactics were; how you went public with it; how you went, privately, to the political power-brokers to deal with it; and how important it is to New York City and to students here, as a preservation story. That’s about an hour and a half—[laughter].

Q2: —in ten minutes.

Q3: —in ten minutes, right. Do you want to go home now?

Papert: I think I want to explain to you, first of all—you may know that I am Tony’s father. I say that so you won’t think I’m picking on him when I tell you—I’ll start this off by giving you my take on preservation battles, because, as Vicki suggests, I’m old and cranky, I have changed my views on all this. I am generally, in matters of politics, in withdrawal these days, under any circumstances—as we all are, I’m sure, since last Tuesday.

Something that trouble me, as I get older, are what I think are hurtful things to the preservationist movement. I make my grandson, or son, responsible for what I think is a metaphor for the worst—and I’ll just quickly tell you about it, and then you’ll know, generally, where I’m coming from.

I really do want to apologize for being late today. As I told Vicki, there’s a slight preservationist twist to that, because our offices are in the old McGraw-Hill Building, one of the great national landmarks. And national landmarks, when you buy them there’s an investment tax credit available to you. If you renovate them you get a big tax deduction, in the course of the renovation. So all the worst sides of the real-estate business—which, as far as I’m able to tell, since I changed my major thirty years ago, and more or less got into the real-estate business, the not-for-profit side of it—is a horrible business. Real property, you might have learned in the last thirty years, brings out the worst in everybody.

An example of what can happen in a building like this is that the building is now, because it’s been flipped a couple of times—and because people were looking for the investment tax credit, never thinking as a Jerry [I.] Speyer, a rare bird, does when he buys a great building like the Chrysler Building or Rockefeller Center. Rockefeller Center’s architect’s earlier job was the McGraw-Hill Building. The latest hands it’s fallen into are guys just trying to flip it again and make some money, so they don’t want to spend any money on it. One of the things they won’t spend any money on are the elevators. So I waited fifteen minutes to get on an elevator. I knew I wasn’t going to make the three-forty-five I promised you, but I could have made the five of four, maybe. Instead I was sitting there, screaming in the elevator.

Now where was I? The preservationist movement. Is that what we’re talking about today? And my metaphor.

My shameful son-in-law, my son, defended a building in Carnegie Hill. It was a one-story, brick building, a taxpayer, that was—I hope we don’t have a religious-values problem with this talk, because it’s slightly dirty. This building was what everybody thinks of when they hear brick shithouse. It was a brick shithouse, and it was sitting right on the corner of Madison Avenue and Ninety-First Street. For years, everybody in Carnegie Hill—and I was raised in Carnegie Hill, and I was part of the formation of Carnegie Hill Neighbors—was trying to get rid of this.

Finally, a developer comes along to develop it, hires a very good architect, Charlie [Charles A.] Platt, who used to be a Landmarks Preservation commissioner, was chairman of the Municipal Art Society Preservation Committee—a perfectly good architect. Architecture is a personal matter, anyhow. But he was certainly a responsible architect.

He builds the building. He designs the building. The neighborhood, as a result of the Carnegie Neighbors hard work, has put a limit on the height of buildings. It has reduced the height of buildings from something to something else. The buildings on the other three corners of this intersection of Ninety-First and Madison are all—one’s, I think, a twenty-story building, one’s a seventeen-story building, and one’s a fourteen-story building. The guy proposes a seventeen-story building, and immediately, gets a cutback. Okay, that’s life in the city—a twelve-story building.

Then led by Tony [Anthony C.] Wood, I have an awful feeling, the neighborhood begins to enjoy the idea of a preservationists’ battle, without any regard for whether the battle has anything substantive—we New Yorkers just love to get into an argument about something. We want to mount our case. That’s the fun of it. And if you go to community board meetings I hope you’re not all community board members, you will find that the meetings are all attended by people who have boring jobs during the day, they come in at night, and they can dump on somebody.

So this was not Carnegie Hill neighbors—which started out as a very, very responsible neighborhood organization desperately trying—the first thing we learned was to keep as far as we could away from [Manhattan] Community Board 8, one of the really horrible community boards. We managed to get the heights lowered, and we got the whole district designated as a historic district. We did a whole lot of good things.

Q3: This was what year, just to put it into context?

Papert: Well, that was all in 1969. I was then in my other life, and we did a lot of political advertising. The campaigns that I worked on were Robert Kennedy’s, and Kennedy somehow inspired me to want to get involved in public service—something I didn’t know a lot about. So for the first time in the history of this neighborhood—I don’t know if you know a lot about—are you all preservationist students?

Q2: Many of them are.

Papert: Well, Carnegie Hill is a neighborhood whose central plan is called peaks and valleys. On the avenues are taller buildings, and on the near blocks are lower buildings. The lower buildings provide light and air to the towers on the avenues. Madison Avenue, when I was a kid—which was in the early Seventeenth Century—had tall buildings, and Park Ave [Avenue] has always had fourteen-, fifteen-story buildings. So when poor Charlie Platt comes in with a seventeen-story building, or sixteen-story building, whatever it is—is it a good building? Because it could have been a horrible building.

But it was a good building, and some little subset of Carnegie Hill Neighbors, with some, imaginative thirty-year-old investment bankers, decided they would have some fun with this. They enlisted Woody Allen—you know that name—who had just bought a house on one of these streets. Woody Allen claims that the afternoon sun is blocked by this sixteen-story building. Well, by the time the sun comes around to where it’s going to block his building, it would block somebody—the light behind somebody standing on the sun side of this, the sun is way down by then. So that was not an argument. But Woody Allen who really got into this decided that he was really going to enjoy it, and he made a movie about this, if you will remember.

They schlepped this thing through three Landmarks Preservation [New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission] hearings. The guy finally, I think, is reduced to eleven stories, and then this group sued to stop him from occupying the eleven-story building because, it says, the Landmarks Preservation Commission must, before they ever rule upon the appropriateness of a building go for an Environmental Impact Statement. Well, anybody—these are all the politics in New York. Environmental Impact Statements are, by and large, a joke. They are the ways in which, the thing that everybody knows at the beginning, are wasting months and months of people’s time, so that neighborhoods can strengthen their positions, or the developers can get more money.

Anyhow, that’s the story. Finally, they went to court, the court threw them out. I don’t know whether—did they win the appeal? They lost the appeal. As well they should have. And when they went into this everybody—the Landmarks Preservation Commission, the Landmarks Conservancy, the World Monuments Fund, the Municipal Art Society—everybody told them to withdraw the suit, because it was going to hurt the landmarks movement. But they had a court rule that the Commission has to do an Environmental Impact Statement, they would have had to have almost doubled their staff to do it, they didn’t have the staff to do that.

Anyhow, those kinds of fights, I think, are something, if you become preservationists and run into these battles, you want to be careful of. I think if we are not careful in picking our fights, if we don’t have a really good reason to battle for a building, then all the buildings are lost. If everybody battles over everything, the ones that really matter get washed away. So that’s my little shtick. I say that to my loving offspring.

Let me tell you another slight political story. The question of sacred sites is a very interesting one and this will segue into a subject that I know interests Vicki, and I know interests Ken as well, this question of celebrities in these fights. But there was a bill—what was it called? The Flynn/Walsh bill—to exempt from all landmarks rules church buildings. The argument wasn’t really a religious right—it sounded like what we sort of hear of today of all kinds of symptoms that had such a horrible impact on the election. The danger, of course, is that once you exempt somebody from the landmarks law, then you open the door to everybody being exempted.

Anyway, Kent Barwick dragged [Jacqueline Kennedy] Onassis up to Albany and we went from office to office. In every office, not only were there state senators and state assemblymen, but their families to come and meet her. It was just marvelous. And she really cares about this stuff as you’ll hear later for Grand Central. There is not the slightest doubt, and I think I know it as well as anybody, it would not have been saved without her. The city would not even have appealed the bad lower-court ruling without her. Anyhow, she had that irresistible quality, and won them all over. When the Municipal Art Society, after she died, gave a dinner at Grand Central, Caroline [B. Kennedy] made a speech and said that her letters that her mother wrote on behalf of these causes sometimes embarrassed John [F. Kennedy Jr.] and her, because when you read one of those letters—nobody could say no to one of those letters, whatever the subject was.

In any event, she saved us from Flynn/Walsh as I remember, and undoubtedly her presence—not as a celebrity, because in the case of Grand Central she was really the brains of that whole operation—

Q2: Should you talk about that?

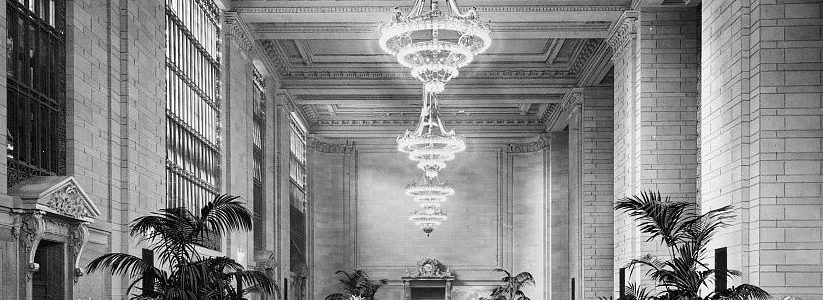

Papert: Nobody made a move. She had the best political reflex you’ve ever seen. So her presence, obviously, when we would give rallies under Commodore Vanderbilt’s statue, and she was there, the whole of Park Avenue, the Park Avenue ramp, would be there jammed. Of course, the great story of Grand Central is that when the thing went to the [United States] Supreme Court, somebody cooked up the idea of a Landmark Special that would leave Grand Central, go to Washington [D.C.], and be there for the day of the oral arguments. We forgot that the trains did not leave Grand Central, it left Penn [Pennsylvania] Station. But that didn’t stop anybody. The whole gathering was there, and we then slipped into taxis and went to Penn Station, and got down to Washington.

When we arrived at Union Station, the place was absolutely mobbed. Pat [Daniel Patrick] Moynihan and Joan Mondale were there. But as far as the press was concerned, Joan Mondale could have been a Girl Scout selling cookies and Pat Moynihan could have been a porter. They only wanted to talk to Onassis. The whole story got to be, Jacqueline Onassis has come back to Washington. And although this is a matter of some dispute—because when Justice [William J.] Brennan—we gave him a dinner, he asked for questions, and I had the audacity to ask a question about this. I said to him, “Did the public attention to all of this make any difference in the court’s decision?” He was outraged at such a suggestion. But we knew better because one of the justices had told, I guess, Ralph [C.] Menapace that one of the things that influenced them was the extraordinary amount of public interest. The only possible way they could have known that was that that night we arrived, all the Washington stations had on, “Onassis coming back to Washington to hear the oral arguments.”

So there are many nice ways to get lucky, like the likes of Jacqueline Onassis, but they’re not going to grow on every tree, as you can imagine, to help in these causes. But essentially, I think, what wins these fights—what got her involved in Grand Central—is some really appalling, outrageous attack on a landmark that means something.

Q3: Could you talk about that, and set the stage as to what was happening with Grand Central, and what the threat was? And why she got involved?

Papert: Yes. Grand Central was owned by the Penn Central [Transportation] Company and a very smart guy ran the company. It was a public company, they were having hard times elsewhere, and they made a hardship claim. As you know, for landmarking to stand up, it has to be insulated from the attack that it is a taking private property. Nobody ever wants private property to be taken by government. I think that’s probably a good reflex. But in this case, he said that—and you could argue—the arguments against landmarking, for landmarking, have to do mainly with appropriateness, is what you want to do appropriate, or is what you want to do caused because there are legitimate economic reasons to do it.

So Penn Station’s argument was that they couldn’t afford to maintain it as a station, because there just weren’t enough revenues anywhere, and they had to knock it down or build something above it to get the revenues going. One of the unsung heroes of the universe—Mimi [sic] [Nina Gershorn] Goldstein I think that’s her name, who was a lawyer at the [New York City] Corporation Counsel—got on the case and fought this with out-of-the-box thinking. Something that I commend—a slight aside.

The world today, it seems to me, seems to be all about process, never about purpose. I think the idea of saying something that hasn’t been said before is almost verboten. You go into big board meetings, even board meetings at my beloved Municipal Art Society, and say something eccentric or iconoclastic, everybody frowns at you. Next to one of the MAS great heroes, Giorgio Cavaglieri, now a ninety-year-old architect—I am the other elder. When I raise my hand at board meetings, Kent Barwick and Philip [K.] Howard frown [laughter] There is nothing I can say—I could say, “Hello, Kent.” And he would do—what was I going to say next? Now, how did I get here?

Q2: Mimi Goldstein.

Papert: Here’s Mimi’s take. She said, “In calculating the economics of the station”—what the expenses were, what the income was, and why it didn’t work—“they did not take into account the value of that station to somebody running the railroad.” Because you have to have a station for the railroad to come in, so you have to assign some value to that, and when that value was added, it turned out that Penn Central was making a fair return. And on that argument hinged the reversal of a lower-court decision. When the lower court Judge [Iving H.] Saypol ruled that the City had absolutely no right to stop a wholesome property owner from doing anything he wanted to with his property, Penn Central threatened the city that if they appealed that decision, and it delayed their going to work on whatever they were going to do—demolish it, or whatever they were going to do—that it would cost them so much money that they would sue the City for $80 million. These were the days when $80 million meant something. Today it does not.

Onassis wrote a letter to him. If I had thought about it, I would have brought it. But you can find it in [John] Belle’s book, because we got a copy of the original, handwritten one, and it is one of those just irresistible letters. [Abraham D.] Beame then agreed to appeal, and MAS pushed very hard. We won the appeal and it went to the Supreme Court, where it stood.

Q3: When did the campaign start, to save it?

Papert: I guess right then. Well, Tony would now the date.

Q1: Believe it or not, that happened just before I moved to New York. But I think it was ’76 through ’78.

Papert: I think it was earlier. Was the ruling ’78 or ’76?

Q2: The Supreme Court ruling was ’78. But I think it started in ’74.

Q1: Well, there were several phases. You had wonderful storefront in Grand Central—

Q3: Well, that’s what I’m curious to tease out of you. You knew the threat. Then did you sit down and call together a group of people, and—

Papert: Well, I think what actually happened is that Onassis read about it—in my version of it—but she called somebody, and asked whether she could get into the fight. She was asked to do so at the Municipal Art Society. Then she became, really, the managing partner, the general of it all, without even the slightest doubt. There wasn’t a move that we would make that we didn’t talk to her and she wouldn’t have the right take on it—quite brilliant, in fact.

Q3: So were you doing public outreach? I know that there were fire trucks, and you had a storefront. Maybe we could talk about that.

Papert: Well, I was in this sort of—I’ve come to think, now that I’m out of it, a really nasty advertising business. My wife, whom I dragged from the magazine business into the advertising business, believes that advertising is the root of all evil [laughter]—and you can really make that case. Because if you start with the media—which is really getting pervasive and horrible—the crime, then, is selling advertising. I think you could attribute to all that advertising, and the programming that gives the audiences what the advertisers want, why we’ve become a sort of dumbed-down country. I never know with Tony, because he could be for George [W.] Bush, he’s so perverse—

Q1: That’s going too far.

Papert: But it seems extraordinary to me that anybody living in this country, who read a newspaper or listened to the radio or anything, would not think—maybe they don’t like [John F.] Kerry, but nobody could like George Bush. But he’s going to win that election. It just seems to me to be absolutely off the wall. And I think we all share—were wounded by it.

Incidentally, I had dinner with a friend the other day, and in the course of the conversation—which was all we were talking about, my friend said, “I’m going up to hear Bob [Robert] Herbert.” Whom the [unclear]—of the City of New York has cooped up at the Century [Club], and my wife—we both thought, “Do we want to hear any more of Bob Herbert?” We love Bob Herbert, but do we really want to hear him after the election? Or should we just turn them all off for a while?

But I think what we should all be thinking about—and I’ll give you this assignment, and I’ll take it on myself—what is it going to take to not let Karl [C.] Rove fulfill what he wants to do? He’s said what he wants to do. He does not want this administration to be part of an eight-year cycle. Political cycles are really eight-year cycles. He wants to be at least a thirty-year cycle. They have designs on this country, in my opinion, and in order for us to be a republic it’s going to take more than any of the usual suspects, and way more than the usual approaches to these things. And anybody that thinks—a subject I do know something about, advertising—anybody who thinks we’re going to do better ads than somebody else is just nuts. That’s not what’s going to happen. We need a focus. We need a way of approaching this that hasn’t occurred to anybody yet. Because when that moment comes, Karl Rove is going be the enemy, and he’s ninety-nine times smarter than anybody working for Kerry, that I can see. So we have to think of something, a new take on it.

So think about that. It’s hard to think of concepts.

Q2: How did you go from advertising to preservation?

Papert: Well, because when—we were the first public company— oh, you don’t really want to hear this story—but anyhow, we liquidated the company, but kept enough money to get into a lawsuit. I won’t explain what the lawsuit was, but the lawsuit took years to deal with, and at the end of the lawsuit, before the end of the lawsuit which I wound up winning, I became rich enough that I could get out of advertising. I was going to be fired out of the advertising business, so I wouldn’t have stayed under any circumstances, and I didn’t like it.

But I could afford it, and I thought it would be fun to spend my life doing something interesting and responsible. I started this company that began as a way to rescue the west end of Forty-Second Street. Jackie Onassis and I started the company, because we were both dismayed, as New Yorkers—born-and-bred New Yorkers, or New Yorkers being in New York as visitors—what had happened, particularly to this Seventh-Eighth Avenue block, and further block. The Seventh-Eighth Avenue block used to be the heart and soul of New York, and that was absolutely true—

Q2: Was that in the ’80s?

Papert: It was in the ’80s. At the end of the ’80s it got better, but this began in the ’70s. This company was started in 1975, but I’d been working on it between ’70 and ’75.

Anyhow, back to preservation, which you’re much more interested in.

Q3: The Grand Central component of it—you talked about advertising being the bane of our society right now. But oftentimes, when one talks about a political preservation battle, the first thing you say is, “Go to the editorial board of The New York Times.” Or, “Go call the City Section. Get an article, get that public campaign going.” So isn’t it a double-edged sword? I want to know from you the battles exactly.

Papert: I don’t know that we did any specific advertising, but I was called upon, because I was thought to be a creepy advertising person, to find ways to hustle things. The first hustle I took to a friend of Tony’s and mine, and a super hustler in the Jim Morton [phonetic] mold, which is a great compliment, Suzanne Davis [phonetic]. Suzanne Davis has uncles, and the uncles do—whatever you want, Suzanne has an uncle who does it. So we first got J. Walter Thompson to be our volunteer advertising agency, and they immediately came up with a great line, which was, “No more bites out of the Big Apple.” Nice line. Naturally, Suzanne had an uncle who made ties. So eight hours later we had 32,000 marvelous ties, one of which, now in shreds, is worn by Kent Barwick almost every day of the week.

But they were just wonderful. They were a little apple with a white bite out of it, on a blue background—a red apple with yellow—just a marvelous tie, and I think we sold them for $7. We made money, and it was just terrific. Then we figured, well, we’d got this thing behind—

You know, Grand Central is the kind of preservationist fight that you want, because when you, say, go to the editorial board of The Times, The Times would come to us—because everybody in the city wanted us to win that fight. Those are the kinds of fights you want. You want fights where there’s a really good, non-participatory democracy; non-NIMBY [Not in My Backyard] argument for doing it. Because if we don’t largely limit ourselves, our energies, to those fights, then we’re not going to have any ammunition left when the serious ones come up.

Q3: That comes to a question that we were going to talk about later, perhaps. My segue, or question, for you is, many of the battles in preservation have been about these large, municipal, public buildings. As preservation has evolved, we also have battles for residential neighborhoods, such as Gansevoort Market. I’m curious, from your take—first of all, are the tactics different? But it sounds like those battles, perhaps, are diluting, or am I putting words in your mouth?

Papert: Well, it depends. Just because I was in business, in a profit-making business for a long time, I look for recycling opportunities, where somebody can recycle a landmark and it will do them a lot of good. It is true—I think the great thing about New York, or at least the great thing about Chicago, New York has sort of lost this, is to have a nice, new, tall building next to a nice, old building. I think that contrast is what makes neighborhoods nice and human. I think that’s what interests people. I think that when you walk down Sixth Avenue, for example, where every building is the same—that’s an awful thing. But when you see P.J. Clarke’s, next to that Skidmore [Owing & Merrill] building, on Fifty-Fifth Street and Third Avenue—that funny-looking, funky little thing humanizes it all. Then you don’t mind the building.

I think there are a lot of arguments—and a way to win those arguments, just incidentally, is—I’ll give you an example of one that could have been a great case, but somebody flubbed it. When the Biltmore Theatre—which was a landmarked theatre but a dysfunctional theatre, because it didn’t have good support space—had a big fire X years ago, so it was just sitting there, a burned-out building, not doing anybody any good. The Manhattan Theatre Club, one of the good companies, bought it, and hired Jim [James S.] Polshek, one of the good architects of this city, to do a restoration of it. And to make it incidentally not a nine hundred-seat theatre but a six hundred-seat theatre, so there would be room for support staff.

Since I’m never going to shut up, if you go to the theatre, there’s a very good play there now, called Reckless. There are very few good plays in New York. We send—because we now build theatres on Forty-Second Street, so people call us for theater tickets because we’re on everybody’s house list. The only play, the only musical, that I could recommend with impunity is Chicago. If you have not seen Chicago, I want to tell you that my wife and I have each seen Chicago twenty-one times. And when Emmy [Emily] Papert came back from San Francisco six months ago, we all said, “Well, let’s go to the theater. What shall we see?” And we all said, “Let’s go to Chicago again.”

But Reckless is a really nice show, and I recommend it to you, a very interesting show. Not a great show, but if you look for a great show you’re really sad [laughter]. But it’s not one of these terrible, contrived ones.

Anyhow, the Biltmore is part of a mischievous little scheme that the city has cooked up to do the theatre owners a favor—which is that they can transfer the air rights from mid-block theaters to Eighth Avenue. A big stretch. The argument was, “Well, then they won’t demolish the theatres,” which is just nonsense. If anybody has a theatre that works they’ll never demolish it, and if it doesn’t work, who cares if they demolish it?

But, in any event, that, which was worth, I think, fifty to sixty million dollars just for the Shubert Organization, which allows for the transfer of air rights. So here comes a site on Eighth Avenue which is itself the subject of new zoning, and a guy, right next to it, on Eighth Avenue, is going to buy those air rights and transfer them to the corner, and he’s going to get—next—on the other side there’s a fire station, and they have some air rights. So with all these air rights, gifts from the city—so the city has a real interest—this guy is going to build a fifty-two-story building.

Now what is the city’s interest in this? The city’s interest should be that this building, which is going to be the first one to benefit from this accumulation of air rights, under which the city has some control, should be a marvelous building. Not one of those horrible, banal buildings that New York City zoning laws allow terrible builders to do easily. So at the Municipal Art Society, the Preservation and Planning Committees are gathered to hear the presentation from Polshek’s people, and from Peter Claman, who is the architect for the tower. Peter Claman is an inside-out architect. When you want to build a residential building, and you want all the toilets one on top of the other, so it doesn’t cost you a million dollars to build it, you hire Peter Claman or Costas Kondylis. But that doesn’t mean that they’re design architects—they are not. So what you need if you want a good building, a good residential building, is you hire a good residential architect. He decides what the silhouette’s going to be, what the shape of it is going to be, and then Peter comes in and organizes the stuff inside, that no one can really complain about.

Anyhow, we hear from Jim, and we hear from Peter’s guy, and we look at the drawing, and it’s a horrible building. It’s the thing I hate most in this world which is a four-story, retail base. If every building in New York had a four-story retail base, there would be eighty-three Duane Reades you’d have to go into. And so Al [Albert K.] Butzel and I cooked up this idea: Why don’t we find out whether the developer—because it was just in the drawing stages—why don’t we find out whether he could get Polshek to do the skin on this tower, and therefore have two jobs, essentially, on the same site. The question was whether Jim would do it, because Polshek ordinarily doesn’t want to work with any developers.

But we called him up and he said sure, he would do that. So Butzel and I go speak to the developer, and the developer, naturally, says, “It’s way too late to do that.” We said, “Come on. How can it be too late? You haven’t even sent anything to the Planning Department.” He said, “Well, there’s a time—we need process.” So we said, “Hold off about it.” By then, the Community Board has brought what he wanted to be a fifty-five-story building down to fifty-one stories, and the [New York City] Planning Commission is allowed to go up to fifty-three stories. We calculated exactly what the cost would be of bringing Polshek in. It was exactly seven-percent more than the cost the would be if he weren’t in, and that’s worth another two stories. The deal was going to be—because when it gets over forty stories, it doesn’t make any difference how tall it is if it’s a good building.

So we said, “Let them have a couple of stories, but make it a great building.” And our beloved Municipal Art Society, when told to go to the Planning Department with the idea, went instead to the developer, believed it when he said, “We can’t do it.” And dropped it. Because that would have been the first, sensible way of finding an incentive for good architecture. And preservationist projects often have the opportunity of making those swaps. I’m particularly these days, very eager to do deals, rather than spend my life in a participatory democracy, which is endless. So it’s something to think about.

Q3: I’m just curious, on that note. What has evolved in your preservation political philosophy that you’re more attuned now in wanting to make that deal, rather than chain yourself to the proposal?

Papert: Well, before I leave you, let me just tell you, a deal was made on Grand Central. In order to make this stand up—this Supreme Court ruling—the city allowed the unused air rights to Grand Central to be moved further north. Now it produced a truly horrid building—the Bear Stearns Building, which is just the biggest building you’ve ever seen in your life, one that has been unremittingly brutal.

But, nonetheless, those kinds of deals, it seems to me, are all right. I think these days—and we’ve seen it in this election—that the best thing you can do is find some if there is any, find some common ground somewhere, and give a little bit if you get something. I think you have to decide what it is you care about most, and then hold onto that, and give them something they care about. This sounds awful and weasely, but it was Pat Moynihan’s philosophy. Pat Moynihan wanted to do—the Municipal Art Society had been working on two projects—this was one I know Tony will disagree on—but they found another solution. It’s sort of an interesting story, I think.

There were two great preservationist projects connected to the Midtown West/Hudson Yards project. To start that project, I understand—which I think was important for them to do—you’ve got to figure out what the other side’s got in mind. Dan [Daniel L.] Doctoroff—whom I don’t even know, so it’s not a personal matter—has fought somewhere along the way, don’t ask me where is this list of things, he fought this, but as you observe the big thought is that after forty years of doing nothing about this fifty-five-square-block area along the Hudson River—it’s simply a wasteland. There are no neighborhoods there. This is not a case of Bob [Robert] Moses wiping out a neighborhood to build the Cross-Bronx Expressway, when he could have moved the thing two blocks north or south and saved the neighborhood—because there’s nobody living there. There’s just nothing going on there.

So Doctoroff comes up with a really brave idea, I think, to do something about it. All of us had been kvetching about that, and if you had a dollar for every study that’s been done about what you should do about it—it used to be called Clinton South, you could rebuild the South Bronx. It’s just an endless studies.

So Doctoroff comes up with this, and MAS has two very intense interests. One is that Forty-Second Street, the north anchor of all this, which is a treasure trove of preservation icons, from one end to the other, and no one can see them. Visitors come to New York, the bus service is so dysfunctional you can’t get on a bus and go back and forth see them. So Moynihan, and our company, and the Municipal Art Society, have for years been trying to get a modern, light-rail system to replace the buses. I should have brought a picture of this.

I don’t want to waste time with this, but it got all the way through ULURP [Uniform Land Use Review Procedure] which is a very hard thing to do, and then mean [Rudolph] Giuliani disappeared it, for no known reason. It’s come back a little bit now, because they need it to get over to the west side. So that was one thing MAS wanted and the other thing they wanted, another Moynihan project, was the Moynihan Station, which has been treading water in an awful way. For eight months, a small group of us had been saying to MAS, “Listen, just make a deal with Doctoroff. Say to him, ‘We’ll support the stadium, if that’s what you’re fussing about, if you’ll do the Moynihan Station, and put in a Forty-Second Street trolley.’”

And they did better than that. I’m not going to tell you what it is, because I’m not sure whether they’ve shown it to the city yet. That’s been a struggle too. They have a brilliant new way to rearrange the furniture, just simply marvelous, that makes the whole fifty-five-block area so interesting and such a treasure for the city. Such a great, new neighborhood for the next twenty or thirty years or whatever it is, that nobody would say, “Well, I love it, but if you leave the stadium in, I’m not going to support it.” Because who cares about the stadium. I mean— it’s a stadium. Maybe it’s too big, maybe it can be made a little smaller, but it can’t be—the city can’t leave this thing empty for another forty years, because there’s a stadium there.

So that kind of a deal may be in the offing. I’ll just tell you but you may not repeat it—I think the city has now heard it and we didn’t want anyone to hear it before. What’s going to happen is that you’re going to come through a great, vaulted room, which will be at the west end, the Ninth Avenue end of the new post office—the new Moynihan station—something comparable to Grand Central and what Penn Station used to be. And you’re going to go through some great doors, and what you’re going to hit is a great, sort of Champs-Elysées Boulevard that goes right to the Hudson River, and on either side of this boulevard are the twenty-eight million feet of commercial towers. So they’ll all be there rather than all over the place, and what makes it marvelous is A, you don’t mind them being there, and B, all those tenants are coming in on the Long Island Railroad, so if you can’t get the number 7 [subway] line extension, he doesn’t need it.

Then they put the residential stuff somewhere else and reduced the bulk of the convention center. They have ways to simplify the stadium, as well. That, I think, was presented by David [M.] Childs last—maybe Monday—and if the city— if Doctoroff likes it, he will then say, “Well what about the stadium?” and we will say, “Look. You probably can’t get a vote to support the stadium because, like everybody else, half of our board members don’t want a stadium, but we absolutely won’t oppose the stadium, because we don’t think the stadium makes any difference here.” We think it’s not important. You should think when you get into preservation battles, what really matters to you and what doesn’t matter to you and be prepared to give a little bit and you’ll get a lot further.

Q3: In this instance, though, we were talking about earlier—the public campaigns, of going—the train up to Albany—you’re not public with this, really—

Q2: I think it points out the difference between tactics. There’s no storefront advocacy. There’s no loading of buses. There’s no postcards. There isn’t that building of a constituency for this plan. This is a really behind-the-scenes, solution-finding effort on the part of MAS.

Papert: That’s correct. I think that’s right.

Q2: I think what might enlighten the audience is why do you feel that it’s a stronger strategy in this case, and why—

Papert: Well, it depends. I think what you want to do is reserve going to The New York Times editorial board and going to the press until you’ve exhausted the other possibilities. Because once you do that, once you throw the gauntlet down, then you’ve got a battle going on. And just as a practical matter, my guess is I don’t know this, either, but my guess is that with this [Michael R.] Bloomberg administration, they’re not going to care about the editorial. And in fact, I think one of the sad, by-products of this pervasiveness of the media is that every politician knows that the editorial you write today fish get wrapped in tomorrow, and they don’t care [laughter]. I think people know that. There are great front-page stories, but almost no stories have legs.

That’s one reason I’m going to see Bob [Robert] Herbert. When Bob Herbert gets on somebody’s case, he doesn’t leave them alone. Did you follow the story about the guy who had a bad drug rap in Texas? He just wouldn’t leave it alone, and they finally got a court down there to reverse it.

Q2: So you think it’s just an ineffective strategy?

Papert: It depends.

Q2: In this case.

Papert: Grand Central?

Q2: No, in the case of the west side. Advocacy—

Papert: My bet would be that Doctoroff will get what he wants. And to make that furniture arrangement as human and as interesting as you can, and now you’ve got a really good idea and we said, “If you show this to Doctoroff and they don’t like it, and then you want to go to war, go to war.” And that’s fine.

Q3: So, just in a nutshell, the tactic was, the MAS did their own charette so to speak, or vision of what it should look like, to counter the city’s arguments.

Papert: Yes, but don’t put it in that pejorative a way. They were not satisfied that the city had really solved its problem, and they did exactly what you said. They put the arm on some good architects, some on the board. They worked on their own, just as they did on the Moynihan Station in the first place. Moynihan wasn’t getting anywhere with it, and Philip hired a very good architect, and they got Hugh Hardy and [David M.] Childs in and finished the whole thing up. And that helped move it along.

Q3: It’s interesting, just in terms of hearing the older strategies versus the newer strategies, it sounds like, as preservation organizations have evolved, and have more money to be able to do those types of renderings or hiring architects, the tactics have changed, for the bigger groups.

Papert: I think you will find—maybe it’s because I do it all the time. I named myself the king of schnorers [phonetic]. I used to be the king of pornography: I would ask anybody for anything. I think you will find that good architects, good designers, good researchers and good everything, like to get involved in these kinds of projects.

Q2: But only certain kinds of groups have access to them.

Papert: Well I don’t really think so.

Q2: Because in the case of the west side, you have the Hell’s Kitchen Neighborhood Association, which has developed its own plan and—

Papert: That’s fine. They can do it. But theirs isn’t going anywhere, either.

Q2: Why?

Papert: Because I think that—I saw the Baruch [phonetic] one the other day, and I heard about it. There’s something that seems to me impractical, after three years of debating, to say, “Yes, we like it, but put the stadium somewhere else, and change the direction—” Do you want to start all over again?

Q3: Do you think that helps, as a political strategy to have those other groups, and then the MAS plan is kind of superlative?

Papert: Well, no, I think it would be—

[INTERRUPTION]

Papert: —and they have money, so they come up with their own plan. I think that the way to do these things, and particularly now, because I think Amanda [M.] Burden is better than a lot of planning commissioners—she’s aware of this stuff is to try to work it out with them; just tell them what your problems are. Say, “Look, you have a problem with the convention center because it looks like the Berlin Wall. It’s just that you can’t see or get to Hudson River.” And we did that by speaking to Bob Boyle who’s a friend of mine, and who is very open to fixing—as long as his program works. In a lot of cases, you can’t go to the developer and say, “Listen, it can’t be apartments, it’s got to be this or that.” He has investors and put money in this thing, and he runs some numbers and this is what he wants to do. You have to figure out, to the extent that you can while accommodating what they have in mind, what you have in mind, and you’ll find that that it works a lot of times.

As I said at the beginning of this—that that fight up on Ninety-First Street was exactly wrong on every single count. It was wrong, but it wasn’t remotely a preservationist fight. The economics were just off the wall; that they would go to a court and say to a guy who had just built a building eleven stories tall that he couldn’t occupy the building, because somebody didn’t do an Environmental Impact Statement.

Q2: Interestingly—I was actually hoping to return to this. We probably should spend another ten minutes and then answer some questions from the audience.

Papert: They’re all asleep.

Q2: They’re on the edge of their seats.

In the Citibank Tower issue, at Ninety-First and Madison, the use of a celebrity—I think the group that organized that was looking at the Grand Central Terminal fight from the ’70s. And in some ways—

Q3: In some ways it’s like Grand Central.

Q2: In a way, it is.

Q3: Don’t hit me.

Papert: I’m going to kill you all. That’s exactly the wrong way to think—that this is all techniques. You start these things with a sound, substantive purpose. Don’t start with, “If I can use this technique, well I’ll do it. Well if I can’t—” Screw technique. Technique is ruining this world, and it’s long since ruined the country. Anybody can—you can get Woody Allen, and the developer will get somebody else.

Q2: But as you know, looking at a lot of the preservation groups, and having worked with many of them closely, I think that tactics have become a checklist, and you look at the past stories, like Grand Central, St. Bart’s, and all those, and you think, okay, postcards to senator; check. Try a celebrity; check. Get an editorial [laughter]. And how do we get out of that?

Papert: What I’m saying to you is, “Think outside the box.” This is what I want you to do for the election—

Q2: Oh, don’t stop now.

Papert: You start thinking process, and these techniques are all part of a process, and you are doomed. Think purpose. What will win the cause for you is that you are really passionate about it. Because if you’re passionate about it, that passion is what will win the day. You only feed this idea that these round-heeled, elected officials, the second they’re elected they’re running again, or trying to suck up to you—that they’re going to save you. They’re not going to save you. They’re only going to save themselves. If you’re going to go down, go down fighting for a cause you care about, don’t give in to all that stuff. When you have the cause, once that’s set, then you’ll find that these other things naturally gravitate toward it. I think. That’s certainly what happened with Grand Central. It’s what happened with St. Bartholomew’s.

Q2: Can you tell that story a little bit?

Papert: Well, the St. Bartholomew’s story is an absolutely marvelous story. The pastor of St. Bartholomew’s, Tom [D.] Bowers, a marvelous import from Atlanta—a non-New Yorker. He lands here, and has a great reputation for being a fundraiser in Atlanta. A developer says to him, “If you will give us or sell us your community house—” which is just on the south side of it, “—we will build a tower there, and we will give you $7 million a year in rent for your land.” Well that was clearly an appropriateness case. Would a huge tower dwarfing and trivializing St. Bartholomew’s be appropriate? Well, it wasn’t appropriate. But that’s not the way you fight these fights. The way you fight them from the other side is, you start out by saying, “Listen, appropriateness is not the question. We have an economic problem here.” Because economic problems are harder to defeat.

So Brendan Gill and I had breakfast with Tom Bowers and—he’s another one of the heroes of all of this—and in an hour lunch the cost of the unattended, deferred maintenance work that had to go on—which started at $250,000, was $7 million by the end of the lunch. It was going to go $30 million—whatever it had to be to make a good story. So MAS did its own study and found out that $250,000 was closer to whatever the numbers were, so when they made that argument it didn’t stand up. I think if it were me again, if I were way younger, getting into these fights, the first thing I would do is find a good lawyer. Because I think if you’re relying on politics to win these things, you’re kidding yourself. The only chance you have of saving things that shouldn’t be demolished, or winning whatever you want, is that you have a legal case to do it. Because the politicians will run roughshod over you one way or another. I believe that. And I think with this crowd in Washington—

Let me tell you a scary Washington story, a sister to the Walsh/Flynn bill. We hear that Orrin [G.] Hatch, as I discovered, one of the real powerhouses in the United States Senate—powerhouse meaning that he’s an enforcer. You cross him, and you’ll wish you weren’t in the United States Senate. He wants a federal bill to be passed that will exempt all church properties from land use regulation. Well, who would vote for that? Because he’s saying you find Onassis, and go to see people. Hatch works it out that there will be what is called unanimous consent at the United States Senate—which means that there will be no hearing, no vote—the Senate just passes it, and all it takes for it not to be allowed to be a unanimous consent is that if one single senator says, “No, I don’t agree with unanimous consent,” then that will ruin the whole process.

Not one of them has the nerve to do it, and the thing is unanimously passed. Now let me ask you a quiz question. Orrin Hatch is from Utah. Who do you suppose owns more land in the state of Virginia than anybody but the State of Virginia?

Q3: Utah.

Papert: The Mormon Church [The Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints]. This is nothing but a Mormon Church deal, the same way Flynn/Walsh was a Catholic Church bill. So this had nothing to do with values, with anything. This just has to do with the real estate, we’re back to the horrible real-estate business. So you want to bear that in mind, and you will soon be introduced to one of the heroines of all these fights, who was a lawyer. If I were to go back and do arguments about preservation, I would only do it if I had a legal case, I mean if there was serious opposition to what I wanted to do.

Q3: The St. Bart’s case played itself out—

Papert: St. Bart’s was [unclear] because they filed a hardship case, and the court found it insufficient. Afterwards, along the way, Onassis and I went to visit Tom Bowers, just to see if we could sort of make peace there, and butter would not have melted in his mouth. He was so happy to see us, he was so nice to us. That was a Friday. The following Sunday he delivered a sermon at St. Bartholomew’s about Onassis not knowing anything about poor people. Why should anybody take her advice? It was really awful.

Then, a couple years later, Bowers had left and returned to Atlanta or something, there was a new pastor, and he calls up the Municipal Art Society and says, “Listen, you have your annual meetings every year. We would love you to have them at St. Bart’s, because we really want to make up for that, for that fight.” So the deal is—in fact, it wasn’t that much later because Bowers is still there. Bowers calls up and says, “We want to make it all up.” So the deal was, “Yes, we’ll come. Thank you very much. That’s very nice. It’s just that you can’t talk about the battle.” And Bowers can’t not talk about the battle. So he makes some speech, and Brenden then makes some speech, which we have on tape somewhere, the thrust of which had to do with moneylenders in the temple. He was so angry at Bowers, and it was such a marvelous speech. There’s a lot of room for good emotion and good stuff, but if you really want to get things done, find a good lawyer. There’s one right there, I think.

Q2: I think what we should do is get some questions. Do people have some questions out there?

Q: I actually have two, but first of all I wanted to ask Fred—you have a different take on preservation. The reason I’m asking is because I’m new to this preservation thing, but going your way, with picking your battles. I’m weighing what’s important vs. what could win? Does that make sense?

Papert: Yes, but don’t—but it doesn’t have to be that. Weighing what’s important from what isn’t so important. You always want to win but some of them you can’t win. I’m not asking you to give up, but don’t waste all your ammunition on marginal cases. There are a lot of marginal cases out there.

Q: Well, then, I guess I’m trying to figure out how to tell what’s marginal. Because I guess we get taught that everything’s important. I mean, not everything, but if one person says it’s important, then—

Papert: So the lawyers are going to have to come back into it. We have a [New York City] Landmarks Law in New York, that was established by the Supreme Court case. Before that Supreme Court case, landmarking was not—is that not right, Dorothy?

Dorothy Miner: Well, it was a brand-new law in 1965 in New York, but had been going other states since 1931. But what the Supreme Court did was it gave [unclear] to even an individual designation and not just a district, and in a case where a major amount of money had been denied on a development. What the Supreme Court really said was that the commission was constitutional, valid, in denying that permit for a fifty-five-story tower above Grand Central, in the process it upheld the New York City law which designated individual buildings as well as districts.

Papert: I attributed—I gave credit to somebody who’s name I maybe got wrong. Was it Mimi Goldstein?

Dorothy Miner: Nina Gershorn?

Papert: Who’s now a judge.

Dorothy Miner: Yes. Nina Gershorn.

Papert: What was her name before it was Gershorn.

Dorothy Miner: Goldstein. Nina Goldstein. But that was in the Appellate Division. Len [Leonard] Koerner then argued in the court of appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court.

Papert: Wasn’t she the one who thought up the idea that there were substantial, unaccounted-for revenues in the fact that it was a train station.

Dorothy Miner: They had failed to give a value to the spaces they needed to run the terminal.

Papert: Why should buildings be preserved? Because they have some meaning to somebody, or because the architecture has meaning to architects. The building has some special worth that has value to the public; if you look at it, if you get the sense, when you go by it, that there is a scale and the feeling of history and all that. The law now allows that those buildings be preserved; that they are landmarks. So your process would be, if you see such a building, and it is a landmark, then you have a legal case. If somebody wants to put something that’s too big next to it, I think there probably are a lot of organizations you can come to with that.

But if it is not a landmark, then your approach would be to find out whether or not you can get it landmarked—an absolutely legitimate thing to do. But I don’t think do it if it’s a building you like, but it has no legal reason for being protected. I wouldn’t spend my life—you can go and ask the developer, not to do something mean to it, but that’s about all you can do. I just wouldn’t waste a lot of time. You should because you’re young enough to waste time, I haven’t got any time to waste [laughter]. By my standards, the first thing to look for is a good legal reason that they can’t do this, and you don’t want them to do this. So they must do what you want them to do. You will find this. I mainly don’t want you to get into the habit of just letting the idea—climbing onto the barricades and hanging signs up and all that stuff.

Look at this election is a measure of people’s ability to terrify candidates who just hang signs up that say anything. Those little things on the back of every car—”Support our Troops.” What does that mean? Is there someone who doesn’t support the troops? That’s one of those polarizing—but you’ll decide what you want to do about that.

Q2: Any other questions?

Q1: Everything you’ve said about picking your battles; choosing what’s important to you; the need for passion; getting a good lawyer, is exactly what takes you to a situation like the Madison Avenue Ninety-First Street battle. The difference is that the people who are making the choice of what their passion is about have reached a different conclusion than other people, and preservation has gotten more decentralized, more democratized. When I started preservation, under your tutelage, it MAS and Landmarks Conservancy that really set the tone, set the lead. Now there are I don’t know how many preservation groups around town.

So I guess the challenge becomes, in a de-centralized preservation movement, how does one begin to try to coalesce, to get back to a sense of shared priorities, or is that just a thing of the past?

Papert: I think that [unclear]. You didn’t stand up to those guys. In fact, you supported them, [unclear]. You either let a new organized be formed, to [unclear] historic district, but there’s nothing but those people spreading out. You are the one work whom nobody would have ignored. You even allowed them, the new group, to enlist Joan [K.] Davidson. That’s awful.

Q1: Well, in defense of Joan Davidson, who’s not easily misled, it perhaps shows that there is some validity—

Papert: Now you’re wrong. You’re wrong. When Joan heard what it was about, she wanted to get off of it. But Joan is too polite to do that. You recognized it. You’re one of the guides. You knew that was a bum rap. It was stupid.

Q1: Well, that’s not to debate that here. I will say that—

Papert: Some of us are right and some of us are wrong. I think you’re wrong.

Q1: I would like to underscore that one of the reasons it is wonderful we’ve had you as a guest tonight is to allow this philosophy to be heard. It’s a very important perspective that needs to be taken into consideration. It very much reflects where preservation has been for many years, where it may be going, and where it may not be going.

Papert: You can’t make a silk purse out of a cow’s ear or whatever it is [laughter]. You didn’t want me to say these things and I said them. And you’re stuck with them [laughter].

Q1: That’s why we invited you. It’s history in a whole new form.

Q2: Also, the idea of perspective, especially for young people getting into preservation—it’s very important to not just accept what is being done now, after forty years of preservation in New York, as dogma; as “This is the checklist, go out and be fruitful. Fight your battle, and don’t forget the postcard to your senator.” I think it’s very important that young preservationists be introspective about all these issues. And it’s troubling and hard for them, I think, knowing my students as I do. There’s a lot to think about, and where do you find the passion, and how do you use the passion to try to save a past that is a legitimate past? I think some of what you’re talking about with Ninety-First Street is that, in your view, that was not a legitimate fight—

Papert: That was my neighborhood. I mean, I hustled my neighborhood. I didn’t go to somebody else’s neighborhood with that story—

Q3: The light and air issue—I know from my prior days at the Landmarks Conservancy, often things would come up as an issue, and is it a preservation issue or is it a zoning, light and air issue? And where do you take that position. That’s one of the things that has evolved, because it has become a bigger issue, like light and air was, and I don’t know if—

Q2: In other words, the two are being misapplied.

Papert: I think that’s absolutely accurate. Because a lot of those low-rise buildings that we wanted to preserve—I own one of them, on the other side. I lost all my sun entirely when a thirty-six-story building went up. But a lot of the ones that one would have argued to preserve weren’t really worth arguing about. The skill which in that case is worth arguing about.

Q3: Right—

Papert: And you have to sort it out a little bit. I would just go up to Columbia and take their preservation— get a master’s in preservation [laughter].

Q2: I think we have time for one more question. Is there a final question? Final thoughts?

Lisa Ackerman: Maybe Ken could talk a little bit about how he feels all this applies to what is going on in either of your sacred sites, or the consortium of preservation groups working downtown.

Q3: I was fortunate in the sense of having to deal with the RFRA [Religious Freedom Restoration Act] separate from my day-to-day bread and butter, good job of going out giving grants to religious institutions around the state. That being said, in a macro view, religious institutions don’t know how to maintain their buildings properly, have years’ worth of deferred maintenance, and they’re in a crisis in this country with the preservation of religious structures. It scares me, from a political point of view, that there are these faith-based initiatives, and how money is going to be allocated for that.

That being said, Fred speaking here today has been very helpful in understanding what I’m trying to do in Lower Manhattan, or what I’m charged with doing in Lower Manhattan. Because we have taken a lot of the tactics that have been used over the years, and applied them to certain degrees, as well as applied a lot of other tactics which are much more—your question about compromise. There were some compromises made that I’m not sure I’m happy with personally, but, collectively, the group I work for wanted it that way. It, in some ways, has been successful, but it’s been mostly the issue—What I’ve learned, from shifting from politics, to the political arena, it’s who you know, physically. It’s how you get to someone’s ear, and your job is to get to that person’s ear, who is the decision maker.

The big question in the room, as you were saying—who to call and how you do it—it’s how you call to make those relationships. I was fortunate to have this incredible name-recognition behind me with these five groups, but a smaller, grass-roots organization really has to work at picking up the phone, getting credible, getting the imprimatur of a local paper that gives them credibility. Those are the techniques that, no matter what, are going to help people along the path of preservation politics.

Papert: I think that’s correct. Carnegie Hill Neighbors’ great quality was that he tried very hard to be sensible, not overreach. We cultivated all these relationships, because we knew that the moment would come when we would need some vote, I suppose. But I think mainly we just understood what was good about the neighborhood, we understood what wasn’t going to get better, we picked our targeted areas rather carefully, and I think we did very well with it. In time, all these organizations, I suppose, get tired, don’t they? Then others have to come along. It’s a little disheartening to think about. When these young people come in—it’s sort of like the staff at the Municipal Art Society. You get the feeling that they don’t know anything. Every time there’s a presentation made to the Planning Commission, somebody there who doesn’t know a lot has written this beautiful thing, but it doesn’t—but what’s it all about? But that’s my geriatric crankiness.

Q2: Well, thank you so much for being here.

Papert: Thank you very much.

[END OF INTERVIEW]