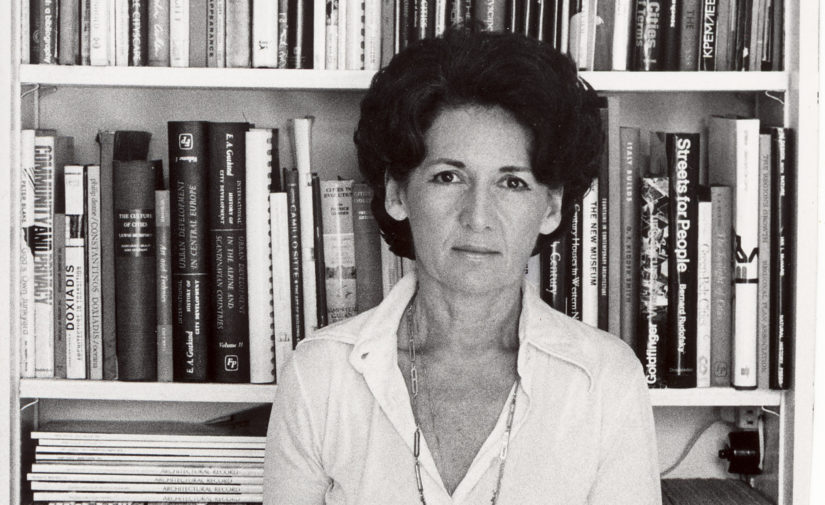

Ada Louise Huxtable

Ada Louise Huxtable was a renowned architecture critic who wrote many passionate articles fighting for the preservation of architecturally significant buildings in New York City.

Ada Louise Huxtable, a renowned architecture critic, was born in New York City in 1921. She received an art degree from Hunter College and went on to study at the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University. She began working as the assistant curator of the Architecture and Design Department at the Museum of Modern Art, under Philip Johnson’s tenure, in 1946. In 1959, Huxtable authored her first book, a series of walking tours of modern New York buildings entitled Classic New York and Four Walking Tours of Modern Architecture in New York City.

Huxtable joined the staff of The New York Times in 1963, and is noted for establishing the field of architecture journalism while there. She worked at the Times until 1982. Her tenure there was significant for New York architecture, and especially for preservation. Her articles served as catalysts for change, and radically raised public awareness of both the built environment and historic preservation.1

Aside from being a distinguished critic (she was awarded the first Pulitzer Prize for architectural criticism in 1970), Huxtable was also very involved in preservation advocacy.2 Between December 1961 and the passage of the New York City Landmarks Law in 1965, Huxtable wrote over 20 pro-preservation editorials that were invaluable in educating and exciting the public about historic preservation.3 She commented on numerous preservation controversies, including the demolition of Pennsylvania Station, alterations to Grand Central Terminal, the preservation of Carnegie Hall, and the controversial redesign of 2 Columbus Circle.

More recently, Huxtable was the architecture critic for The Wall Street Journal and published her last book—entitled On Architecture: Collected Reflections on a Century of Change—in 2008. Huxtable’s last published article condemned the proposed changes to the New York Public Library building at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street.

Ada Louise Huxtable died on January 7, 2013. She was 91. Huxtable bequeathed her archives and estate to the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles.

Ada Louise Huxtable wrote many passionate and engaging articles fighting for the preservation of architecturally significant buildings in New York City. Many were unsigned editorials written for The New York Times editorial board.

One of the first preservation causes that Huxtable advocated for in her editorials for The New York Times was the case against the demolition of Pennsylvania Station. She wrote numerous articles to inform the public of the atrocity of Penn Station's impending demolition. Writing for the editorial board of The New York Times, she called the demolition a “monumental act of vandalism against one of the largest and finest landmarks of its age of Roman elegance.”4 She also wrote:

"And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed."5

This quote continues to be invoked by preservationists in their advocacy campaigns to this day. Also in reference to the demolition of Penn Station, Huxtable wrote that the: “…peculiar combination of higher building costs, and lower architectural standards of today, a lack of vision–all these factors are making our cities uglier and more ordinary every day.”6

Huxtable also advocated for landmarks legislation in New York City. Writing for the editorial board, she explained the basics of and advocated for the creation of the Landmarks Law.7 She explained that the landmarks commission worked on persuasion, and she asserted that this was not a legislative answer.8 She wrote: “Mayor Wagner signed a proclamation establishing 'American Landmarks Preservation Week in New York City' as part of a national and international program to protect landmarks that neither he nor the city has any power to protect."9 She made the public and government officials aware of the necessity for the Landmarks Law, which was eventually created in April 1965.

Huxtable continued to write against the demolition or altering of cherished New York City landmarks. For example, she wrote against a proposal to construct a bowling alley below the ceiling of the Grand Central Terminal waiting room, which would have reduced its height from sixty to fifteen feet. When this proposal was turned down because of zoning restrictions, Huxtable also fought to protect “further desecration” of this building.10 In addition, Huxtable advocated for saving Carnegie Hall and adaptively reusing it for cultural and civic use. She advocated for Senator Mitchell’s bill, which was designed to help preserve this great landmark.11

Furthermore, she argued against the introduction of a $500,000 “sidewalk café” that Huntington Hartford wanted to construct in Central Park.12 She wrote persuasively about the need for parks in New York City, writing “Every Foot of the Park,” which appeared in The New York Times on April 19, 1960. The café proposal was turned down. She also opposed the introduction of a large veterans' memorial at the north end of Union Square Park, raising the important question, “Do private groups, no matter how worthy, have the right freely to propose and carry through public or quasi-public structures of this scale and importance?”13 The veterans' memorial structure was never built in Union Square Park.

Huxtable continued to discuss historic preservation into her later life. She used the campaign to save 2 Columbus Circle to argue that an intransigent approach to preservation is not beneficial. “One wonders at what point New York's civic groups lost their vision, just when they decided nostalgia and trendy revisionism overrode a positive contribution to the city's cultural and architectural quality."14 This campaign in particular led Huxtable to write about what she considered to be the negative aspects of preservation. She pointed out the existence and problem of preservation for the sake of preservation. “There is a great deal more at stake than this one building. When preservation distorts history and reality in a campaign of surprising savagery, it signals an absence of standards and an abdication of judgment and responsibility. It has lost its meaning when we prefer a stagnant status quo."15 She fought against preserving the facade of 2 Columbus Circle: "Inspection has found the facade so badly deteriorated that it can't be saved; it would have to be rebuilt—a copy or reproduction would have to replace it."16 The campaign to save 2 Columbus Circle was ultimately unsuccessful.

- Ada Louise Huxtable Archive

The Getty Research Institute Research Library Library Services

1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100

Los Angeles, CA 90049-1688

Phone: (310) 440-7390

Fax: (310) 440-7780 - Oral History with Bronson Binger, Joyce Matz, Lorna Nowvé, Henry Hope Reed, and Norval White

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Tel: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 265.

- “Interview: Ada Louise Huxtable,” PBS, 29 February 2016

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 284.

- “Farewell to Penn Station,” The New York Times, 30 October 1963.

- Ibid.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008).

- “Landmark Legislation,” The New York Times, 3 December 1964.

- Ibid.

- “Anything left to preserve?” The New York Times, 24 September 1964.

- ”Bowling Over Grand Central,” The New York Times, 10 January 1961

- “Saving Carnegie Hall,” The New York Times, 21 March 1960.

- “Every Foot of the Park,” The New York Times, 19 April 1960.

- “Atrocity at Union Square,” The New York Times, 29 June 1962.

- Ada Louise Huxtable, ” The Best Way to Preserve 2 Columbus Circle? A Makeover,”The Wall Street Journal, 7 January 2004.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.