REMEMBER THAT PRESERVATION LAWSUIT? KEEP YOUR RECORDS!

January 16, 2020 | William J. Cook, Vice Chair

Why Legal Archives Are So Important for Future Advocacy

The Archive Project is the only preservation organization in the United States that focuses on documenting the archives of people associated with the historic preservation movement. Although the Archive Project concentrates on the continuing evolution of historic preservation in New York City, it provides a blue print for preservation-related archive projects everywhere. Since becoming involved with the Archive Project, first as an oral history interviewer for the “Through the Legal Lens” oral history series, and then as a board member, I have learned that the lessons of the past remain not only relevant to preservation as a way to understand the rich tapestry of history, but also as a legal advocacy tool.

It is increasingly important to collect legal archives to inform future legal advocacy. I will explain my background in legal research and how archives inspired my interest—and perhaps others—in historic preservation law. I will then share specific examples of how the Archive Project’s archives have bolstered my legal advocacy in support of saving historic places by helping me develop strategy, hone arguments, and persuade historic preservation commissions and judges to secure preservation wins.

Archival Inspirations. As a lawyer who studied legal research in the mid-1990s, the South Carolina Legal History Collection at the University of South Carolina School of Law provided my first encounter with archives. Bookshelves with leather-bound volumes, manuscripts, portraits, papers, and memorabilia surrounded an antique table and Queen Anne armchairs on a Turkish carpet. It was exciting to read about legal legends who participated in controversial trials and examine their papers, along with other published sources dealing with the legal, constitutional, and political development of the state. This experience provided valuable insights into the minds of judges and policymakers as I learned more about the context of their respective eras through newspaper clippings, transcripts, telegrams, and notes.

Around the same time, I discovered the Archives and Special Collections room of the Charleston Library Society, the third oldest membership library in the nation. From colonial-era letters to literary manuscripts of people of national historic significance such as George Washington, John Marshall, Henry Laurens, and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, the Library Society’s Archives hold some of South Carolina’s greatest cultural treasures.

The Library Society’s treasure that most inspires me is John Locke’s original manuscript copy of the Fundamental Constitutions of the Carolinas, which he authored in 1669 while serving as secretary for Lord Ashley Cooper, one of the Lord Proprietors of Carolina. The document laid the groundwork for the arrival of the first permanent English settlers to South Carolina. John Locke was the foremost 17th-century English philosopher. His work, which found wide acceptance in London’s Middle Temple where several Founding Fathers studied law, was grounded in the humanism of his day and became the philosophy known as modern liberal theory. Locke’s liberalism ushered in the Enlightenment and provided the intellectual underpinning of the American Revolution, the Declaration of Independence, and the United States Constitution. Reading his original manuscript transports a reader back in time. Much like I and my law students drew inspiration from Locke’s manuscript when I was a law professor teaching a course in constitutional law, so did Justice Sandra Day O’Connor of the Supreme Court of the United States. O’Connor visited Charleston in 2009 to promote her civics initiative called “Our Courts.” During that trip, O’Connor said one of the things that impressed her the most was seeing Locke’s manuscript in the Library Society’s vaults. She understood his value and influence on the drafters of the Constitution, which she swore a judicial oath to uphold. One should never underestimate the ability of archives to teach, reach, and inspire a broad range of audiences.

Archives as legal tools. A common definition of “archive” is a collection of historical documents or records providing information about a place, institution, or group of people. Archives provide important legal insight into how lawyers and judges think, for not everything makes it into a legal brief that is filed in court. Like a map, a written court opinion does not show all of its underpinnings. Two archives that have played an important role in my practice as a preservation attorney are NYPAP’s oral history interviews and archival collections, and the legal advocacy archives of the National Trust for Historic Preservation at Georgetown Law Center. These archives have been especially important to my law practice when I have had to defend local governments against attack from regulatory takings challenges.

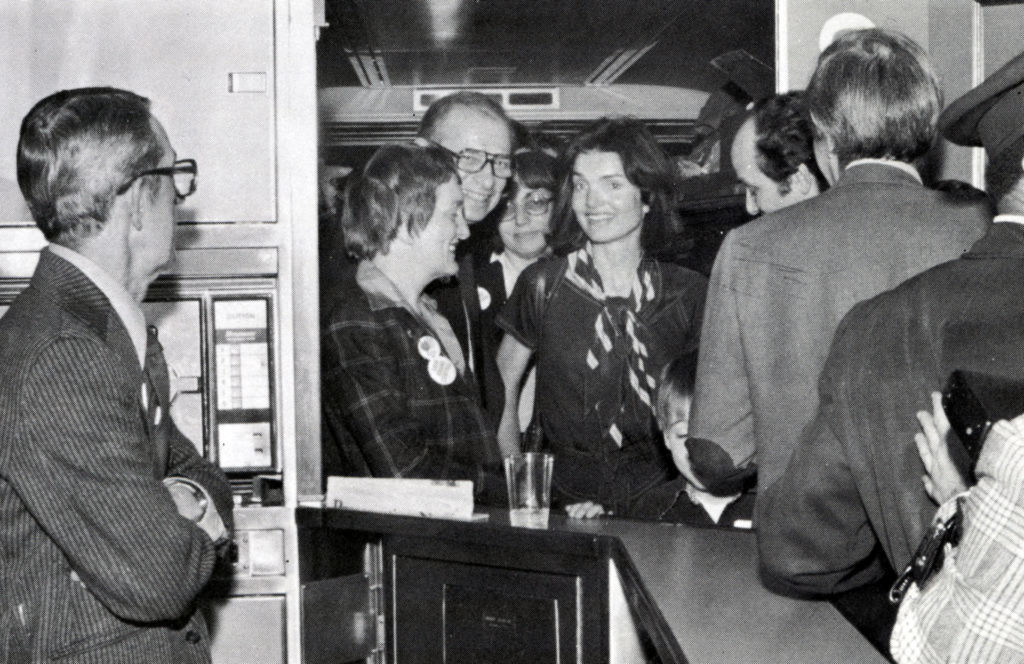

As every preservation lawyer or advocate likely knows, the most important historic preservation legal case is Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York, decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1978. The Penn Central decision established two important precedents in its ruling. First, it affirmed that historic preservation serves a valid public purpose. Second, the Court established the balancing test that federal and state courts continue to use today to determine whether governments owe compensation to property owners for the diminution of their property rights as a result of land use regulation. What is not revealed in the text of the decision itself is the remarkable story behind the legal challenge. Why did lawyers frame their arguments using certain language? What strategic choices did they make? What social, political, and economic circumstances influenced the litigation? The opinion says nothing about the historical moment where New York City almost dropped its appeal and settled the case during a period of extreme financial stress; how Jackie Kennedy Onassis persuaded the Mayor of New York City to press ahead in defending its Landmarks Preservation Law and Landmarks Preservation Commission; or how the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the lead preservation organization in the nation, wrestled with whether to participate as an amicus curiae or “friend of the court” in support of the City.

In moments when traditional legal research may not help, archival collections can provide answers. For example, the Archive Project’s oral histories with attorneys Virginia Waters and Leonard Koerner—who defended the City at the Supreme Court—make the Penn Central story come alive in a way that secondary sources could never achieve. In an era of reliance on electronic databases such as Westlaw, Lexis, and Google, a preservation advocate can easily locate hundreds of law review articles and other references to the Penn Central decision, along with other forms of legal commentary. Electronic research, however, leaves out many archival sources. Having the ability to access these records means that letters, speeches, diaries, newspaper articles, oral history interviews, documents, photographs, artifacts, and any other ephemera can provide firsthand accounts that add depth to legal advocacy and fill information gaps.

Without Virginia Water’s oral history with the Archive Project, for example, attorneys would not know from reading the Court’s opinion that Penn Central Transportation Co. could not have participated in the transfer of development rights (TDR) program established by New York City to mitigate lost development rights associated with historic landmark designation. This is critical information: even though the Court seems to have viewed Penn Central’s lack of participation in the TDR program as an affirmative choice, it appears to have ignored or overlooked transactional barriers that arguably tilted in Penn Central’s favor. A future court might not do that. Archives matter in preservation advocacy.

Leonard Koerner also once shared with me his recollections of how Dorothy Miner, legal counsel to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission from 1975 to 1994, argued to make sure that the City’s legal briefs focused on the Landmark Law’s applicability to the city. Miner’s decision turned out to be a critical strategic decision then, and remains true today when defending regulatory takings challenges. Leonard also revealed the famous anecdote about himself appearing in the Supreme Court without any notes and shocking his boss who asked to review them in the minutes leading up to oral argument. Leonard replied: “And I wrote on a pad, ‘Mr. Chief Justice and members of the court,’ [the standard opening address at the Supreme Court] and he turned colors[.] I’ve thought afterwards that I should have told [him that I planned to memorize my argument] in advance.” As any appellate judge would tell you, this is a good lesson for any law student or attorney to remember.

Legal archives serve many roles, all of which inform legal advocacy and strengthen preservation advocates’ arguments by helping to tell the full story of a case. Archives educate, inspire, and provide a record of history that would otherwise not be available for current and future generations to discover. Using archives adds another layer of research, time, and occasionally expense, but archival research provides invaluable information in helping advocates and decisionmakers understand a case’s complete history. In recognition of legal archives’ important role in illuminating the evolution of preservation law, saving the records of attorneys and other legal advocates in more intentional ways should be a preservation movement priority.

Will Cook is Vice-Chair of the New York Preservation Archive Project and is Special Counsel at Cultural Heritage Partners, LLC, the nation’s only private law, policy, and strategy firm focused on the preservation and protection of cultural heritage resources.