Mayor’s Billboard Advertising Commission

The Mayor’s Billboard Advertising Commission was formed to investigate and report on the growing aesthetic problem of the proliferation of billboards in New York City.

The Mayor’s Billboard Advertising Commission was formed to investigate and report on the growing problem of billboards in New York City.

December 24, 1912: Mayor Gaynor appoints the Billboard Advertising Commission.

August 1, 1913: The Report of the Mayor's Billboard Advertising Commission of the City of New York is published.

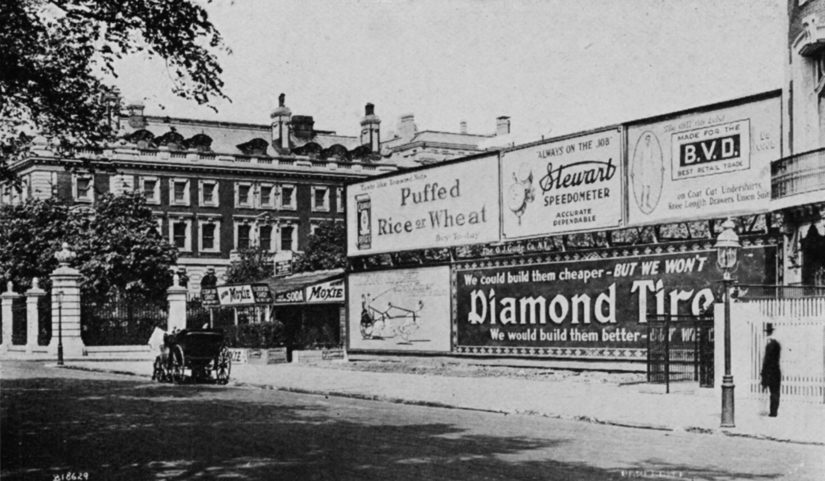

In the late 19th century the City Beautiful Movement emerged on the foundation of improving the aesthetics of cities. As the movement grew, many organizations were formed to fight for this mission. Almost immediately, New York City's proliferation of billboard advertisements came under fire by those in support of the City Beautiful Movement. By 1912, New York City had become a sea of billboards. In Manhattan alone there were 4,600 billboards totaling more than 3.8 million square feet of advertising.1 For many, like Robert G. Cooke, future Chairman of the Mayor's Billboard Advertising Commission, this was unacceptable. Cooke said that great cities were "suffering from abuses incidental to outdoor advertising."2 To combat these abuses, New York City Mayor William Gaynor began inquiring into the regulation of advertisements, first through a report by the Commissioner of Accounts in 1912 and later by the appointment of the Mayor's Billboard Advertising Commission.3 The Mayor's Billboard Advertising Commission was formed at the end of 1912 and sought to further research what was being described as the "billboard blight."4 The commission members were those passionate about the aesthetics of the city, and included Robert G. Cooke, Albert S. Bard, and Reginald P. Bolton.5 Cooke passionately spoke about the situation, stating in a New York Times article, "New York should wake up to the fact that other cities have already attacked the problem of outdoor advertising, and...believe that indiscriminate and unregulated advertising is a serious detriment."6

In August 1913, the Mayor's Billboard Advertising Commission published a report of their investigations. The conclusions reached by the commission were very much in line with the City Beautiful Movement. In the report the commission wrote, "the fullest and most satisfactory handling of the billboard situation cannot be attained until the State constitution has been so amended as to give unequivocal warrant to the legislature and the courts to regulate billboard advertising on the ground of public beauty."7 The report provided a list of 17 recommendations. Several of the recommendations seemed rather far-fetched, but as Christopher Gray noted almost a century later, "from a City Beautiful point of view, the commission made absolutely visionary recommendations."8 Specifically, these recommendations called for "the prohibition of all outdoor advertising structures...on or in the immediate neighborhood of parks, squares, public buildings, boulevards and streets of exceptional character," as well as "censorship of objectionable advertising--not only that which passes the limits of decency (already illegal) but also that which is vulgar by reason of its subject matter or mode of presentation."9 The commission's final recommendation called for a "graded excise tax upon the business of outdoor advertising."10

Ultimately, the City did not directly implement any of the commission's 17 recommendations, as they were considered too extreme. The report, however, was significant in bringing aesthetics and the regulation of them to the attention of the government. Further, Albert S. Bard, the secretary of the commission, devoted much of his life to campaigning for aesthetic regulation. Bard also continued to seek out opportunities "to advance the cause of aesthetic regulation" through various legal means.11 The ideas put forth in the commission's report and Bard's work provided a foundation for the Bard Act of the 1950s.

- The Albert S. Bard Papers

Archives and Manuscript Division

The New York Public Library

Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street

New York, NY 10018 - Albert Bard Archive

New York Preservation Archive Project

174 East 80th Street

New York, NY 10075

- ”The Billboard Question,” The New York Times, 12 January 1913.

- ”Mayors Billboard Commission to Probe Sign Evil,” The New York Times, 12 January 1913.

- Ibid.

- Anthony C.Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 27.

- Christopher Gray, “The Battles Over Outdoor Ads Go Back a Century,” The New York Times, 12 June 2001.

- ”Mayors Billboard Commission to Probe Sign Evil,” The New York Times, 12 January 1913.

- Robert G. Cooke, Report of the Mayor’s Billboard Advertising Commission of the City of New York, 1 August 1913.

- Christopher Gray, “The Battles Over Outdoor Ads Go Back a Century,” The New York Times, 17 June 2001.

- Robert G. Cooke, Report of the Mayor’s Billboard Advertising Commission of the City of New York, 1 August 1913.

- Ibid.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008).