Henry Hope Reed

Henry Hope Reed, a passionate advocate, helped to raise awareness of preservation issues, organized New York City’s first walking tours, and advocated for preserving the original design of Central Park.

Henry Hope Reed was born in Manhattan on September 25, 1915, to a prosperous family with roots in New York and Philadelphia. He attended Harvard University, where he majored in history and met John Barrington Bayley, who would later become architect for the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Reed then spent time as a self-admitted “drifter” and worked for a newspaper in Omaha, Nebraska.1 Later, he traveled to Europe and studied decorative arts with the art historian and curator Pierre Verlet at the École du Louvre in Paris.2

After returning to the United States, Reed became an instructor at Yale in the 1950s, where he met the landscape architect Christopher Tunnard.3 In 1955 Reed and Tunnard collaborated on American Skyline, a book on the history of civic design in the United States that championed traditional design.4 Reed would go on to be author, co-author, or editor of over twenty books and numerous articles and architectural guides.

In 1959, he authored The Golden City, an eloquently polemical attack on modern architecture and apologia for classicism. The book juxtaposes photographs of classically designed buildings, along with richly detailed descriptions of the buildings’ architecture and ornamentation, side by side with their modernist equivalents, a technique which was intended to demonstrate the aesthetic superiority of traditional architecture and ornamentation but also highlighted the need to preserve the historic buildings.5

The Golden City proved accessible and popular and was reprinted with a new forward in 1971. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis said that reading the book was “like finding a long-lost friend or mentor.”6

Throughout his career, Reed consistently championed the forms of architectural design and ornamentation associated with the period of artistic ferment he called the “American Renaissance,” which coincided with the Beaux-Arts and City Beautiful art and civic design movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These styles had fallen almost completely out of favor by the 1950s, and Reed was among the first and most vocal proponents of classical design as an alternative to the unadorned, futuristic architectural vision of modernism (disparagingly termed “picturesque secessionism” by Reed) that dominated architecture in the postwar decades. Above all it was the classical building that Reed celebrated in its proportions and ornamental detail, understanding these buildings as an American expression of a high tradition in Western art. Reed wrote:

“From the grand conception to the smallest bit of ornament buildings were designed and executed with care. Knowledge held no terror; the scholar’s and artist’s hands were one and the same.”7

Reed became involved in civic affairs through the Municipal Art Society, where in 1955 he organized an exhibition on New York’s great buildings of the 19th and early 20th centuries, and the following year began offering what may well have been the City’s first architectural walking tours.

Besides the decorative arts, Reed was deeply learned in many other subjects, including history, horticulture, ornithology, and the French language. He combined his expertise in horticulture and classical design when he was named curator of Central Park (an unpaid position) in 1966. In that position, he was among the first to champion the original design vision of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, an obscure notion at the time that subsequently entered mainstream thinking about park preservation.

In 1968 Reed, with like-minded colleagues including John Barrington Bayley, helped found the not-for-profit organization Classical America, with a mission to reprint classical art and design texts and to publish new works on the classical tradition in art and architecture.8 With the backing of philanthropist Arthur Ross, Reed led Classical America until 2002, when it was merged into the Institute of Classical Architecture. The combined entity is now known as the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art.

Although Reed developed an ever-more curmudgeonly reputation in his later years, he continued writing and speaking publicly on architecture and design until his ninetieth birthday. His final major work, The United States Capitol: Its Architecture and Decoration, was published in 2005.9

That same year, the school of architecture at Notre Dame, with the support of Chicago philanthropist Richard H. Driehaus, created the annual $50,000 Henry Hope Reed Award, which honors a non-architect who has supported “the cultivation of the traditional city, its design and art through writing, planning or promotion.”10

Although the full-fledged classical revival that Reed hoped for has not come to pass, the fervent advocacy of Reed and others of his generation demonstrated the value of recognizing and saving historic architecture, brought classical design out of its postwar obscurity, and helped make classicism and preservation influential forces in architecture and urbanism in New York and worldwide since the 1970s.

Reed was married to Constance Culbertson Feeley, a reporter for the Washington Post and staff writer for the New Yorker, who died in 2007.11

First Curator of Central Park, named to this post in 1966

Henry Hope Reed helped to galvanize the postwar historic preservation movement with a 1955 exhibit cosponsored by the Municipal Art Society (MAS) and the University Club called “Monuments of Manhattan: An Exhibition of Great Buildings in New York City, 1800-1918.” Doggedly committed to celebrating the city’s then-unappreciated built heritage, Reed combed through forgotten archives stuffed into barns in Connecticut and Long Island to find drawings by Ezra Winter, muralist for the Cunard Building, and items belonging to George Browne Post, the architect of the New York Stock Exchange and many other notable buildings.12 He also obtained files from the family of Cass Gilbert and the office of McKim, Mead & White.13

Displayed at the University Club and inaccessible to the general public, the exhibition was nonetheless one of the first, faint sparks to catalyze the public belief that New York City’s historic built environment from before the 1920s was special and worth preserving. After the exhibition was completed, Reed worked with Cass Gilbert’s family to transfer Gilbert’s extensive archives to the New-York Historical Society, where decades later they were used to mount a major exhibition on Gilbert’s work.14

Having attracted attention to the City’s architectural legacy through the University Club exhibition, Reed then pioneered the MAS’s public walking tours to encourage wider interest in New York City’s built heritage. The first walking tour was held in the vicinity of Union Square and Greenwich Village on a wintry day on April 8, 1956.15 The tours proved popular and were soon taken over by the Museum of the City of New York.16

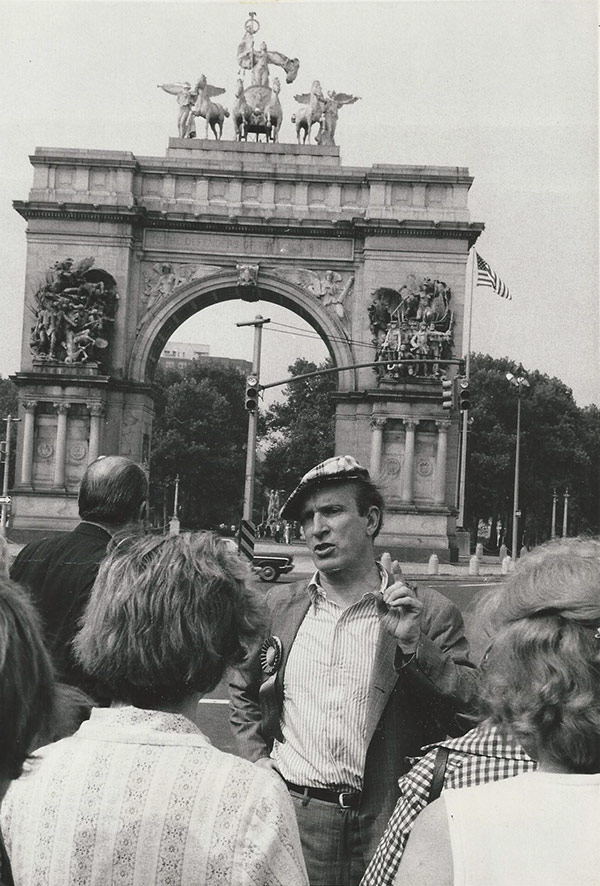

By the 1960s, Reed had developed tours throughout much of Manhattan and as far afield as Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza and Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, which he published in a series of articles in the New York Herald Tribune in 1962.17 Nearly 60 years later, walking tours inspired by Reed are a staple of MAS programming. In a 1998 interview, Reed called the walking tour the “key device” to introduce preservation to the general public.18 In bringing the architectural walking tour to New York City and defining its basic style and form, Reed’s influence was significant. Francis Morrone, an architectural historian who leads walking tours for the MAS and was named one of the world’s top tour guides by Travel + Leisure magazine in 2011, said: “Henry put the idea of walking tours into my head, and he made me see them as something serious, a critical part of the culture of the city. I think I only ever wanted to lead tours because of Henry.”19

In leading walking tours, Reed became known for his witticisms and bombast, which reflected the passion he felt for the subjects of his tours—New York’s historic buildings and landscapes. Harmon Goldstone, the second chair of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, commented that Reed’s walking tours created the awareness and enthusiasm about preservation that was necessary for the Landmarks Law to be passed by the City Council.20

Besides the general support for preservation that his walking tours engendered, Reed’s educational efforts also played a specific role in developing public support for the preservation of Brooklyn Heights, one of the first New York City neighborhoods to wholeheartedly embrace the cause of historic preservation.21 In 1957, Reed and the architect John Barrington Bayley curated an exhibition titled “Classical Brooklyn: Its Architecture and Sculpture” at the Long Island Historical Society Library (now the Brooklyn Historical Society) in Brooklyn Heights.

Reed was then contacted by a group of Brooklyn Heights residents who had organized to fight for, among other things, the preservation of the neighborhood’s historic architecture. MAS then created a special subcommittee, with Reed as a member, with the aim of proposing a zoning ordinance to protect Brooklyn Heights under the recently passed Bard Act. By 1959, Brooklyn Heights and Greenwich Village were the first two New York City neighborhoods to request historic zoning protection from the City Council, although several more years would pass before the desired protections would be put into place.

In the 1960s, Reed turned his attention to Central Park, on behalf of which he played an instrumental, if today largely forgotten, role in laying the groundwork for preservation. He began conducting walking tours of the park, and in 1966, Parks Commissioner Thomas P. F. Hoving named him the park’s first “curator.” The following year Reed and co-author Sophia Duckworth published a book, Central Park: A History and a Guide, which provides detailed documentation of the park’s classical design as planned by Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted, and decries what Reed considered to be modern intrusions not in keeping with the park’s classical design. The book objects strenuously to all manner of insertions, ranging from the construction of the Wollman and Lasker skating rinks to the installation of the Alice in Wonderland and Hans Christian Andersen statues (“Much is made of the fact that children love these statues, but children love the park anyway,” Reed and Duckworth wrote, arguing vainly for the statues’ removal).22 For his objection to a Barbra Streisand concert in the park, Reed was decried by Commissioner Hoving as a “fuddy-duddy,” but The New York Times noted in an editorial that sometimes, it falls to the fuddy-duddy to uphold what is right.23 According to his protégé Francis Morrone, Reed cherished the park but believed that the City had done everything in its power to destroy it, and in his indignant response Reed was among the first to champion Vaux and Olmsted’s original vision as central to the park’s preservation.24 Although Reed’s name was not attached to later park preservation efforts, the substance of his cause would be adopted by the Central Park Conservancy in the 1970s and has largely guided the restoration of the park since that time.

After co-founding Classical America in 1968, Reed’s attention turned especially to the detailed documentation of major works of classical architecture, notably the New York Public Library’s main building, as well as the publication of guidebooks to the historic architecture of the city. His The New York Public Library: Its Architecture and Decoration was updated in 2011 by Francis Morrone and stands as a vital reference work for the future preservation of this building.

Reed’s walking tour notes, correspondence, and other papers have been archived at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library of Columbia University and for years to come will provide a rich resource for further investigation of a key figure in New York City’s historic preservation movement.

- Henry Hope Reed Papers

Avery Drawings & Archives

Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

Columbia University

New York, NY 10027

- Oral History with Henry Hope Reed (available upon request)

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Tel: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org

- Oral History with Otis Pratt Pearsall New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Tel: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org

- Bruce Weber, “Henry Hope Reed, 97, Historian, Is Dead,” The New York Times, 3 May 2013; Francis Morrone, “How Henry Hope Reed Saved Architecture,” New York Sun, 1 August 2005. Article retrieved 9 March 2016

- Francis Morrone, Personal communication, 10 June 2013.

- Richard H. Driehaus, “Reflections,” in The Richard H. Driehaus Prize: Quinlan Terry (South Bend: The University of Notre Dame School of Architecture, 2005).

- Henry Hope Reed and Christopher Tunnard, American Skyline: The Growth and Form of Our Cities and Towns (Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1955).

- Henry Hope Reed, The Golden City (Garden City: Doubleday, 1959).

- Henry Hope Reed, The Golden City, 2nd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton, 1971).

- Ibid, page 83.

- Charles Lockwood, “Dialogue Classicism: An Interview with Paul Gunther,” Urban Land Vol. 66, No. 11–12 (November 2007): pages 40–45

- Paul Gunther, Personal communication, 4 June 2013.

- Paul Gunther, “Henry Hope Reed, 1915-2013,” Architect’s Newspaper, 22 May 2013.

- “Reed, Constance Culbertson Feeley,” The New York Times, 5 June 2007.

- James Sanders, “After Years in the Cold, a Feisty Critic Is Back in Style,” Avenue, February 1985; Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 148

- Margret Heilbrun, ed., Inventing the Skyline: The Architecture of Cass Gilbert (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), page xiii.

- Ibid, page xiii.

- John Sibley, “Neither Snow, Slush Nor Curious Keep Art Unit Hikers From Appointed Rounds,” The New York Times, 9 April 1956.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 152

- See, for example, Henry Hope Reed, “A Woodlawn Pilgrimage: A Cemetery’s Architecture Reflects the Idiosyncrasies of Its Inhabitants,” New York Herald Tribune, 9 December 1962; Henry Hope Reed, “Flatbush’s Arch of Triumph: Brooklyn, Not Washington, Boasts America’s Finest Triumphal Arch,” New York Herald Tribune, 1 July 1962.

- Interview by Anthony C. Wood, June 11, 1998.

- Francis Morrone, Personal communication, 10 June 2013.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), pages 152–53.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), pages 215–17.

- Henry Hope Reed and Sophia Duckworth, Central Park; a History and a Guide (New York: C. N. Potter, 1967).

- Bruce Weber, “Henry Hope Reed, 97, Historian, Is Dead,” The New York Times, 3 May 2013.

- Francis Morrone, Personal communication, 10 June 2013.