Franklin Vagnone

The director of the Historic House Trust from 2009 to 2016 speaks about the Trust’s place in preservation and its relationships with the houses they oversee and the City of New York.

The Historic House Trust oversees the historic houses owned by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Franklin Vagnone, as executive director was focused on their programming component. He helped to reformat their newsletter to a journal and expanded the annual historic houses festival. He also helped to change the fundraising paradigm of the Trust, creating separate funds, such as the emergency maintenance fund, to fulfill different needs for the historic house museums. He shares his experiences with the working relationship of the public/private nature of the Trust and how it’s changed management of the historic house museums in New York City. He also speaks about adaptive reuse in preserving historic properties, particularly historic religious buildings.

Q: So the first thing I wanted to ask you is just, can you tell us your name, what you do here, or what your job title is here, and do you consent to be recorded and give that recording to the New York Preservation Archive Project?

Vagnone: Sure. My name is Frank Vagnone, I’m executive director of the Historic House Trust [HHT] for the City of New York, and I give permission for this to be transferred over to the Archive Project.

Q: Thank you! I guess just start at the beginning, what would you say your job here entails mostly?

Vagnone: Well as executive director, I range anywhere from fundraising to advising all the program areas, and having your hands in everything, everything that goes on here. We’re an umbrella organization for twenty-three historic house museums in the City of New York, so I’m virtually in all five boroughs, all the time, talking with volunteers, executive directors of other houses. The other houses are run by other nonprofit organizations, so we’re this kind of middleman between the city and the historic houses. My job has a lot of diplomacy, a lot of advisement, a lot of communication involved.

Q: So before you came to New York, you actually worked with the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks, right?

Vagnone: I did, you got that right, that’s correct.

Q: Can you talk a little bit about what you did before you became executive director and how that—executive director here—and how that relates to your work now?

Vagnone: Yes, very directly. I ran that organization in Philadelphia for a number of years. We had a handful of historic house museums that we ran, as well as a small volunteer tour guide group, as well as an Elderhostel program. The Elderhostel program was one of the largest in the nation, and the tour guide program was one of the largest in the nation as well. A lot of it had to do with heritage tourism, it wasn’t strictly museum issues, but because we had four house museums and they were about forty-five minutes apart—citywide once again—and it was a lot of various governmental and nonprofit communication, and conversation. In many ways, I cut my teeth on diplomacy and communication in Philadelphia before I came here, because there’s just always—there could be six entities if you had to make a decision at one of the historic houses, or if the walking tour guides needed something, I’d have to contact the mayor’s office and stuff like that. So it was very complicated.

Q: It sounds like you do a lot of the same work here.

Vagnone: Absolutely. That’s why I think that that it was certainly a move up in terms of scale, because I went from four houses to twenty-three, but I also was running some really large programming, and HHT didn’t do programming. So, and one thing you’ll notice in the last couple years is that I’ve started to bring programming to HHT. That’s because that’s my background—programming, as well as historic houses.

Q: Okay. You were talking a little bit about how you have to relate to a lot of different entities, and I was wondering what is your relationship with the Parks Department [New York City Department of Parks and Recreation]? Or HHT’s relationship with the Parks Department?

Vagnone: Sure. Well the Commissioner [Adrian] Benepe is my boss, and then my direct boss is Commissioner [Therese] Braddick, and we work directly with the mayor’s office on many things, because Gracie Mansion is one of our historic house museums.

Q: Okay.

Vagnone: So our relationship is exactly what it states when you’re a public/private organization. I attend meetings with the commissioner, I attend meetings that are with the Parks Department, and I attend meetings that are for the private sector. Half of my staff is Parks Department paid, and half of my staff is salaried by outside money.

Q: Does that usually—does everything usually go smoothly between departments?

Vagnone: Well I would say, because we have such a good relationship with Parks Department, because Commissioner Benepe was actually in charge of the Arts and Antiquities Division when HHT was formed in 1989, so he is very much a part of what we do. Commissioner Braddick was Executive Director of HHT for eight years I think before I came. She’s very much involved and knowledgeable about what we do. As it is right now, and because the mayor’s office has Gracie Mansion, we’re thought of in a high regard because we deal with things that are very directly related to what they do.

Q: So what do you think the most important priority for the Historic House Trust going forward is going to be in the next few years? Or, should be?

Vagnone: Well, of course, there’s the kind of organizational attitude and my own personal attitude, which one do you want?

Q: Either one. Whichever one [unclear].

Vagnone: Organizationally, we really just need to assist the houses in maintaining their public quality, staying open, having a staff—and continuing to grow and increase capacity, both in terms of programming, as well as financial capacity. Personally—unofficially. Personally, there’s a real need for historic houses and the paradigm of management and interpretation to change. It is my goal here, as it was in Philadelphia, and if I go somewhere else, my goal is to really help change what the quality and nature of what a historic house museum is and should be. It really needs to take off the old garment of the traditional 1930s view of historic house museums and put on some really new ideas about why it exists, why it’s even here, why does it matter. Socially, why it existed and started, and it’s no longer the same, same kind of cultural situation, and that needs to change.

Q: So, in view of your own kind of personal views of where programming should go, what do you think is—what do you think you’ve done so far that’s really spoken to that?

Vagnone: Well, not nearly enough, and it keeps me up late at night that I have done enough. Because we’re in the advisory role, we really can’t go in and make changes at the houses. It’s more diplomatic as I was telling you, it’s kind of my background. My friends call me a UN diplomat with my job. The things that I can do, because I can change them—that I have jurisdiction to change them—we’ve really changed, reformatted our newsletter into a journal. The articles and the photography I think are much more in line with what preservation should be delivering. We actually got an award for that. The second thing is a weekend festival that when I came here, they were doing it for maybe two years, and it was kind of a sleepy festival between all the houses in all five boroughs, and it was not themed. And since that time I’ve taken that festival city wide, we’ve gone from zero partners to twenty partners—

Q: Like corporate partners?

Vagnone: —corporate and nonprofit partners. We’ve overlapped with other nonprofit entities like Open House New York. We do bike tours now. A theme is, food related to New York City, and we just got an award for this, because of our partnerships, just this year [I’ve been accepting awards] because of that. Those are two examples of kind of really going in and changing drastically kind of models of how house museums work.

Q: So you talked a little bit about how your relationship with the houses, and how you’re in a nonprofit partnership with them, and you don’t actually have control over what they do you know what can you do, or what do you do to try to work through that?

Vagnone: Well as I said diplomacy, talking with them, communication, but ultimately, and this is not a bad thing, this is where you want executive directors’ heads to be—they need to raise money. One way that we can really help, is to give them money—unrestricted money and restricted money—but the more money we give them, the more we can in a very subtle but open way, help them change where they’re going, and a fair amount of their programming, and stuff like that. So, in some ways money is a big part of it.

Q: Do you have any—what kind of things have you guys done to raise money for the houses, and for your own operations?

Vagnone: Well, in the four years that I’ve been here, we’ve I think drastically changed what HHT’s fundraising paradigm is. As it is now, we hold five funds. The curatorial fund, the emergency maintenance fund, the education fund, the community engagement and so for every bit of money that we bring in at an HHT fundraiser, some of it goes into these funds, and those funds go directly to the houses. So, we turn around and give GOS [General Operating Support] money, which they were doing before, but now I’m hoping that we’ll be able to raise more money because it’s just solely dedicated to turning around and giving checks. Now twice a year we give general operating support checks to the houses curatorially, we have a fund where if somebody needs something they can ask us, and we can buy supplies and things like that. If something happens at the house, in an emergency fashion, we have money that we can fix that. So we’re really on top of that. Also we changed our corporate partnership. Whenever we have a corporate membership, half of that money goes into the general operating support fund for the houses. That’s an example of how we’ve just, really changed. Also every membership that we get, fifty percent of it goes into one of those five funds. So just in the past four years, you will have seen a major shift in, not our mission, because our mission’s always been this, but because of the economy it’s now more money motivated.

Q: Yeah, yeah, you just need the money now.

Vagnone: Yeah. It’s not a bad thing, you know?

Q: Do the houses have to apply for grants from the general operating?

Vagnone: No. The general operating—as long as they fulfill their contractual agreements in their license, which is, get the attendance to us, and fill out a maintenance report and stuff like that, then they get the GOS funds. But, there are some houses that haven’t gotten GOS funds because they haven’t complied with those licensing agreements.

Q: So you do have agreements between yourself and them that are binding legally.

Vagnone: Yes.

Q: Okay. That’s interesting, yeah.

Vagnone: And we have an agreement with the Parks Department, which is binding legally, as well.

Q: Oh, I see how that, okay, so that’s actually—

Vagnone: Lots of layers—

Q: Yeah, very interesting. That sounds like it can get kind of bureaucratic sometimes.

Vagnone: Very bureaucratic.

Q: Let’s see, so, just to get a little bit broader, if you have a second—

Vagnone: Of course, yeah.

Q: What kind of larger role do you think the HHT plays in the preservation movement in New York? Just outside of direct administration of their houses, or the houses.

Vagnone: Yeah, it’s very interesting, because I think what you’re seeing is this kind of this shift, shifting focus a bit. Before I came here, it was extremely well done organization, very high functioning, they saved the houses architecturally, they stopped the water, they were in really, really pretty good condition. And, but not much programming at all. And there wasn’t much of a public presence for HHT. I would say that HHT still stood as a kind of subsidiary department to the city, the Parks Department. Since I’ve gotten here, with those examples that I gave you, we’ve become much more public. Our programming has been much more in your face. Our journal is now being read by a much wider audience.

Q: Yes I’ve seen it.

Vagnone: Our website’s expanded, people from all over downloading the journal on PDF. I would say that it’s growing. To answer your question, on HHT’s place in preservation, I think it’s pretty well set that we take care of those twenty-three houses.

Q: Right.

Vagnone: What I do think is happening now, is that people are looking to HHT as a kind of model for not only historic house museums, but also preservation organizations, in terms of programming, and marketing and stuff like that. We’re just now kind of getting to that point.

Q: So you kind of view yourself as an example of one way that preservation can actually move on from just saving the houses to doing something.

Vagnone: Yeah, and this is an issue, especially with historic houses and stuff, and that is that there is this amazing energy when the houses need to be saved. We have wonderful pictures of every house having vines growing in it before collapsing and all that. So you have all these people and all this money. And then you know, they’re seventy-five years later, and they really don’t know what to do. It’s like they can’t—how many candle dipping classes can you give?

Q: Right.

Vagnone: I come into preservation from an architectural and design background. So I just kind of naturally come about it from a kind of nontraditional way.

Q: Yes. And actually, I think one thing that might be important to get on here also is your own background. I’ve read that not only were you an architect, but also a sculptor, so you’re definitely coming from an architectural, design background. Can you just talk briefly about that?

Vagnone: Yes I will, and everything you say is true, and I will say that right now in this economy, nonprofits have to be creative. And I think probably some of the most successful leaders right now of nonprofits are ones that are bringing disciplines to preservation that aren’t taught in the preservation school.

Q: Right.

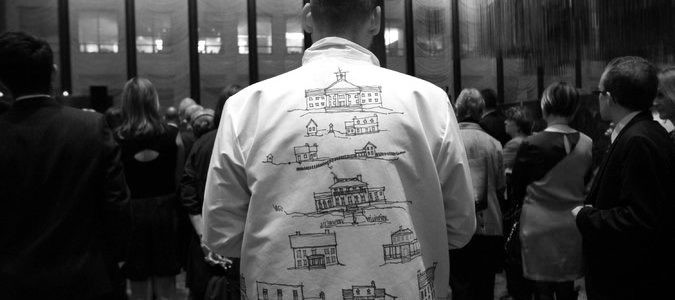

Vagnone: I have an undergrad in architecture and anthropology, and graduate degree from Columbia University in architectural design. I had my own architectural firm. I paint, I sculpt. I bring all of this kind of outside vision to preservation. I really haven’t had preservation training, but in my architectural firm, we did a lot of additions and very sensitive restorations on extremely beautiful houses in Charlotte, North Carolina. And so I kind of entered preservation through the back door.

Q: Right.

Vagnone: I definitely have a sensitivity to it, but I can’t be the one who does the paint analysis. I know it needs to be done, but I’m also not blindly a slave to, for instance, paint analysis or a kind of preservation technique. I’m much more open to reevaluating and reassessing what are the fundamentals of preservation, why do we do it? Why are we preserving what we preserve? And whose stories are the things that are told. I’m definitely coming from a place where I want to reevaluate that. Because I don’t take any of that for granted, because I kind of attack my job as a student would. I just devour it, you know?

Q: Is there anything that you think that should be recorded that I missed? Anything else you want to say?

Vagnone: Well, I will say that the Historic House Trust, I think, does have a pretty solid pilot program for what other cities can do for their historic houses. I think it’s, it’s a very good relationship of public/private. In that we can raise money that the city can’t, and that we can bring in outside consultants that the city can’t and we have a kind of flexibility. All of the historic house museums that are existing alone, you know that are closing, or being sold. All you have to do is look at Google every day and you see what’s happening.

Q: Yes.

Vagnone: For all of those, there’s just as many new house museums that are being formed right now. People are—the houses are collapsing, and they want to save them and turn them into a museum. So this is not going away. There needs to be some kind of business model that actually works. And, from a business perspective, as well as a very strong preservation perspective, HHT works. My hope is that other cities will pay attention to HHT as a means of, kind of coalescing smaller historic sites and houses into one organization with that oversight. So in that way I think it’s very important.

Q: Do you have time for one more question that I just thought of?

Vagnone: Oh sure, yes.

Q: I just don’t want to take up too much of your day.

Vagnone: Oh yeah, you’re fine.

Q: What about adaptive reuse? I know that’s kind of really kind of anathema to a lot of preservationists, but also other—you know there are other preservationists, and especially because you’re an architect, who really see that as a way forward. Do you have an opinion?

Vagnone: Well, again I’m coming about it from outside preservation. I think adaptive reuse is really the only way, and there are a few exceptions that should really keep a thing what it is. Ideally, a thing is used for what it was designed, but come on, historic houses are not used for what they were designed. That’s the problem, is they were fundamentally places you woke up, got out of bed, and went to the bathroom and made a breakfast. You know now, groups of thirty-five kids come and you get a tour around the house. The function is public. It was private. So fundamentally, you know there are questions about preservation, you know, we need to preserve it for what it is. There’s not much that’s preserved, and still being used for what it is. I’m also on the advisory board for Partners for Sacred Places, and a big push there is to keep congregations active in historic churches, but the issue is that historic churches have congregations that are so small, that they’ve got eight-hundred-member congregation rooms, sanctuaries, and they’ve got thirty people.

Q: And preservation imposes a burden.

Vagnone: Yes.

Q: A financial burden.

Vagnone: It does, but it also imposes I think a kind of intellectual burden that keeps people from trying new things. And there’s no question in my mind that, from an urbanistic perspective, preservation really is fundamentally important, because the building as a contributing factor to the streetscape is paramount. There’s no question about that. If the function changes on the inside, that to me is somewhat less important. Now, of course, there, that’s a generalization, and I, yeah, I know. But generally speaking, the larger public ideal of a contributing historic structure would take precedence over its kind of internal function. There’s a [unclear] church in Philadelphia that was saved simply because of, I think an ad agency turned it into their home office. And it’s a fabulous building.

Q: And there’s shops, stores here, yes.

Vagnone: But the interior is completely not what it used to be.

Q: Right, right. And of course it’s no longer serving a sacred function.

Vagnone: Exactly. Now there’s tons of examples of houses being changed over to businesses, and you know, you need to do it sensitively and smartly, and not rip out things, and if you can keep significant ideas, like room sequence and stuff like that. But generally, repurposing the building is, in today’s economy in many ways, the best that you can do.

Q: I think I have one last question. I was kind of aiming for twenty minutes and we’re right about there. So you mentioned the financial crisis earlier, and have you really seen an impact on, for, on the preservation of historic houses due to foreclosures? I guess this is a little bit outside of the HHT because it would apply to people still living in their—

Vagnone: Not necessarily, well, yeah, but not necessarily. You know King Manor [Museum] is in Jamaica, Queens, and that’s I think one of the centers of home foreclosures in the United States, like in 2008.

Q: I didn’t know that.

Vagnone: So certainly just being surrounded by it. A good number of our houses actually went through bankruptcies and were abandoned or sold at auction. Most historic houses have stories just like what’s happening right now. Or abandoned during the Civil War, and you know, Monticello was almost in ruins, same thing with Mount Vernon. So I would say that economically speaking, not as much future historic houses, because I’ll tell you what, that could probably slow down considerably, people trying to turn houses into historic house museums. But what I am seeing is you know my staff is fifty percent what it used to be. Historic house museums are notoriously run on very short financial lines. They’ve had to cut back staff, furlough, I mean they’re really being hit hard right now. So anything they can do, or any money they can get, is very important.

Q: Okay well, unless there’s something else that you really wanted to talk about, that’s kind of all I had for you today.

Vagnone: Okay.

Q: But, thank you for your time, and thank you for talking to us.

Vagnone: Thanks a lot!

Q: And my [unclear] was really happy that you talked to us too.

Vagnone: No problem, thanks.

[END OF INTERVIEW]