Pennsylvania Station

Also known as Penn Station

The demolition of McKim, Mead & White’s Pennsylvania Station, amid public outcry, is popularly regarded as the birth of the modern preservation movement in New York City and the impetus for the Landmarks Law.

The original Pennsylvania Station in New York City was a vast structure that occupied two whole city blocks. The boundaries surrounding the structure were 31st and 34th Streets, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Over 500 buildings were initially cleared for its construction. The original structure was designed by architects McKim, Mead & White, in the Beaux-Arts style, and was erected in 1910.1 The building boasted an ornate exterior, arcade, waiting room, concourse and carriage-ways. Thomas Wolfe, one of the great writers of the 20th century, remembered Pennsylvania Station as a place where:

“The voice of time remained aloof and unperturbed, a drowsy and eternal murmur below the immense and distant roof.”

The building can be described as physically massive. It possessed “Nine acres of travertine and granite, 84 Doric columns, a vaulted concourse of extravagant, weighty grandeur, classical splendor modeled after royal Roman baths, rich detail in solid stone, and an architectural quality in precious materials that set the stamp of excellence on a city.”2 The demolition of the original Pennsylvania Station was announced on July 25, 1961. By the time the structure was set to be demolished, it was dilapidated due to poor maintenance and alterations, and the architectural richness of the building likely went unnoticed by the vast number of commuters who walked through it daily. Nevertheless, as an icon of New York City, the loss of Pennsylvania Station played an important role in shaping New York’s preservation history.3

Pennsylvania Station was never officially designated a New York City Landmark. Demolition began in 1963, and was complete by 1966.

July 25, 1961: The New York Times announces the impending demolition of Pennsylvania Station

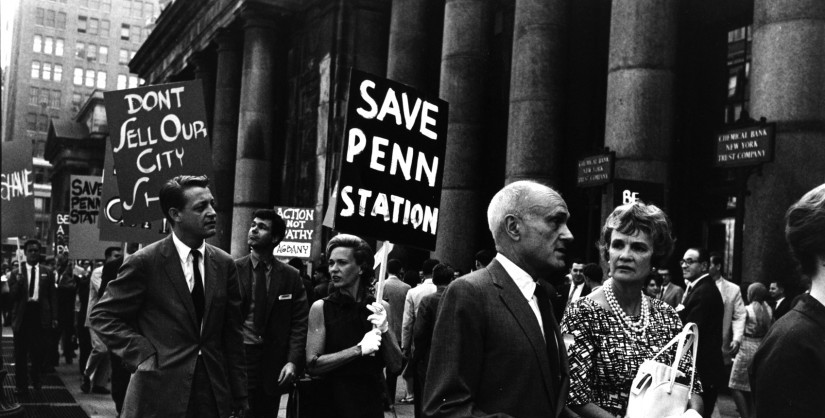

August 2, 1962: The Action Group for Better Architecture in New York organizes a public protest rally to encourage the preservation and adaptive reuse of Penn Station

January 3, 1963: AGBANY submits a brief to the City Planning Commission specifically campaigning against the construction of the sporting stadium that would later become Madison Square Garden on the present site of Penn Station

October 28, 1963: The three-year demolition process of the station begins

Popular perceptions of the history of New York City attribute the birth of the preservation movement and the local landmarks law to the demolition of Pennsylvania Station. The "Myth of Pennsylvania Station" is that the loss of this iconic building first spurred New Yorkers to act in an attempt to gain legislative protection for its landmarks. The truth, however, is that preservation forces had been operating in New York before any threat was posed to Pennsylvania Station.4

In December 1954, the real estate firm of Webb and Knapp (with William Zeckendorf as its president) purchased the option for development of air rights between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, where Penn Station itself stood.5 In 1955, the officers of the Pennsylvania Railroad Corporation developed a plan with William Zeckendorf to raze the station, and replace it with a “Palace of Progress,” a 50-story building that would house the permanent World’s Fair and international merchandise mart. The proposed building would be two blocks wide, rooted and roofed over the present site of Pennsylvania Station. The "Palace of Progress," was to be operated and merchandised by Palace of Progress Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary, with Billy Rose as president and general manager.6 In June 1955, Pennsylvania Railroad Co.’s president, James Symes, and William Zeckendorf signed an agreement to sell the air rights and build a new station below street level.7 In January 1956, Zeckendorf abandoned his original plan for Pennsylvania Station, in the hopes of implementing one on an even larger scale.8

In 1960, The Madison Square Garden Corporation formed with Irving Mitchell Felt as its president, and began plans for a construction over Pennsylvania Station. On July 25, 1961, the front page of The New York Times featured the headline "New Madison Square Garden to Rise Atop Penn Station." The story never even mentioned the impending demolition of the station.9 Subsequently, a second story on the subject was published in the Times, and this time, the press publicized the Madison Square Garden Corporation's plan. The second headline read, "Penn Station to be Razed to Street Level in Project." Preservation-minded journalists, such as The New York Times's Ada Louise Huxtable, proved to be one of preservation's greatest allies during the fight to save Penn Station.10 In her 1963 editorial, "Farewell to Penn Station," she wrote:

"Any city gets what it admires, will pay for, and, ultimately deserves. Even when we had Penn Station, we couldn't afford to keep it clean. We want and deserve tin-can architecture in a tin-horn culture. And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed."11

The Action Group for Better Architecture in New York (AGBANY) formed largely in response to the threat to Penn Station. The group spearheaded the campaign to stop the demolition of Pennsylvania Station. AGBANY organized the public protest rally that took place on August 2, 1962 and employed other methods ranging from issuing petitions and placards, to urging public-minded ownership for the threatened site and suggesting an adaptive reuse. AGBANY sought to politicize the battle by appealing to the City Council and political hopefuls for help.12 AGBANY also submitted a brief to the City Planning Commission on January 3, 1963 specifically campaigning against the construction of the sporting stadium that would later become Madison Square Garden. The brief opposed the construction on the grounds that the proposed space was already designated for a public purpose.13 With no resident constituency directly influenced by the demolition of Penn Station, only several hundred New Yorkers were moved to action to demonstrate against the demolition. New York preservationist Jane Jacobs recalled the weak nature of the protest. She said, "There was no exhilaration to this kind of thing. It was more like a wake. The city was making everyone's life absurd with its goofy decisions."14

The campaign to save Penn Station and to prevent the construction of Madison Square Garden failed, and the actual demolition of Pennsylvania Station began on October 28, 1963. Though the physical destruction took three years to complete, the threat to the station was always a few steps ahead of the potential preservation law that could have saved it. Furthermore, the Wagner administration did not wish to deviate from the chosen course of seeking a comprehensive system of landmark protection in order to save a single building, even if that building was Penn Station.15

Though the history of New York City's preservation efforts began before the demolition of Penn Station, and in spite of the fact that New Yorkers at the time may not have realized the magnanimity of the loss, the destruction of Pennsylvania Station would later become an important preservation icon that rallied people to action. Yet, the successful passing of the 1965 New York City Landmarks Law that potentially could have saved the original Pennsylvania Station can certainly not be attributed to any single event.

- McKim, Mead & White Photograph Albums

Classics (Rare Books)

Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

Columbia University

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, NY 10027

Email: avery-classics@libraries.cul.columbia.edu - Oral Histories with Giorgio Cavaglieri, Diana Goldstein, Stanley B. Judd, Leonard Koerner, Laurel Lovrek, Sanford Malter, Herbert Oppenheimer, Geoffrey Platt, Peter Samton (2004), Peter Samton (2014), Dierdre Stanforth, Norval White, Michael Zimmer

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Tel: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org

- “Penn Station,” New York Architecture. Article retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Thomas Wolfe, You Can’t Go Home Again (New York: Harper Perennial Classics, 1998), page 46.

- Ada Louise Huxtable, “Farewell to Penn Station,” The New York Times, 30 October 1963.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect A City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2007), pages 6-7.

- Lorraine B. Diehl, The Late, Great Pennsylvania Station (New York: Stephen Greene Press, 1987), page 144.

- “New Zeckendorf Project to House World’s Fair,” Washington Post and Times Herald, 7 June 1955; “Zeckendorf Maps New Penn Station,” The New York Times, 30 November 1954; “Palace of Progress,” The New York Times, 9 June 1955.

- Lorraine B. Diehl, The Late, Great Pennsylvania Station (New York: Stephen Greene Press, 1987), page 144.

- ”’Palace’ Plan Out; Bigger One Urged,” The New York Times, 6 January 1956.

- ”New Madison Square Garden to Rise above Penn Station,” The New York Times, 25 July 1961.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routlege, 2007), page 328.

- Ada Louise Huxtable, “Farewell to Penn Station,” The New York Times, 30 October 1963.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect A City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2007), page 302.

- Brief of the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York in Opposition to the Granting of a Special Permit, submitted to the City Planning Commission, New York, NY, 1 February 1963.

- Jim O’Grady, “Voices From the Wilderness Unite,” The New York Times Company, 2003.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect A City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2007), page 302.