Bard Act (1956)

Also known as the Bard Law, the Mitchell Bill, General City Law § 20 new subd. 25-a, and General City Law § 20 new subd. 26-a.

Passed in 1956, this act empowered cities within New York State to pass laws enabling the preservation of landmarks.

The Bard Act provided localities across New York State the authority they needed to pass local laws to protect landmarks, and was the New York State legislation that enabled the creation of a New York City Landmarks Law.

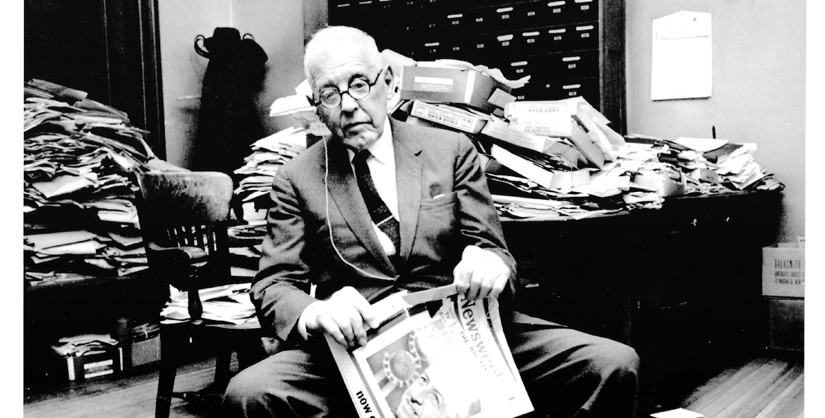

The Bard Act grew out of a concern for civic beauty, a concept which, stretching back to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, inspired generations of architects, city planners, and civic leaders, including Albert S. Bard. Working on the assumption that aesthetic control of private property in the interest of the public good is a legal exercise of the police power, Bard drafted his first version of what would become the “Bard Act” as early as 1913. After over forty years of striving to include aesthetic regulation in the law, in 1954 as part of his involvement with the Joint Committee on Design Control of the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects and the New York Regional Chapter of the American Institute of Planners, Bard crafted a piece of legislation in the form of an amendment to the General City Law. The concept of aesthetic regulation as an exercise of the police power would be legally accepted with the Berman v. Parker Supreme Court decision in 1954. Affirmation of the concept would help to provide a favorable climate for Bard’s legislation, drafted earlier that same year. In 1955, State Senator McNeil Mitchell introduced the bill, which was passed in Albany only to be vetoed by Governor Averell Harriman.

In 1956, the bill was reintroduced and, again, passed by the legislature. The Bard Act was signed into law on April 2, 1956 as new subd. 25-a of the General City Law, § 20. The Bard Law read:

“To provide for places, buildings, structures, works of art and other objects having a special character, or special historical or aesthetic interest or value, special conditions or regulations for their protection, enhancement, perpetuation or use, which may include appropriate and reasonable control of the use or appearance of neighboring private property within public view, or both. In any such instance, such measures, if adopted in the exercise of the police power, shall be reasonable and appropriate to the purpose, or, if constituting a taking of private property, shall provide for due compensation, which may include the limitation or remission of taxes.”

In 1968, this law was amended to more specifically define the types of places for which the legislation provided protection under the law. The word “districts” was added to the list including “places, buildings, structures, works of art and other objects…” This new law became General City Law, § 20, new subd. 26-a, which reads:

“Protection of historic places, buildings and works of art. In addition to any power or authority of a municipal corporation to regulate by planning or zoning laws and regulations or by local laws and regulations, the governing board or local legislative body of any country, city, town, or village is empowered to provide by regulation, special conditions and restrictions for the protection, enhancement, perpetuation and use of places, districts, sites, buildings, structures, works of art, and other objects having a special character or special historic or aesthetic interest or value. Such regulations, special conditions and restrictions may include appropriate and reasonable control of the use or appearance of neighboring private property within public view, or both. In any such instance such measures, if adopted in the exercises of the police power, shall be reasonable and appropriate to the purpose, or if constituting a taking of private property shall provide for due compensation, which may include the limitation or remission of taxes.”

1913: Bard drafts his first version of what would become the “Bard Act”

1954: The threat to Grand Central Terminal creates a feeling of urgency that contributes to the adoption of the Bard Act

1955: State Senator MacNeil Mitchell introduces the bill of the Bard Act, which was passed in Albany only to be vetoed by Governor Averell Harriman

1956: The bill was reintroduced and, again, passed by the legislature

April 2, 1956: The Bard Act is signed into law

1959: The Municipal Art Society recognizes the potential for the Bard Act as enabling legislation and makes efforts to amend the City’s zoning code, pushing for application of the law in “some kind of aesthetic zoning”

1965: The Bard Act is applied to create New York City’s Landmarks Law

1968: The Bard Act was amended to more specifically define the types of places for which the legislation provided protection

A number of growing threats to the built environment and, as a result, the growing support for the protection of buildings in the early 1950s ultimately created an atmosphere that was ripe for this type of legislation. The threat to Grand Central Terminal beginning in 1954 undoubtedly created a feeling of urgency that contributed to the adoption of the Bard Act, as did threats to Carnegie Hall and Pennsylvania Station that occurred around the same time.

Though the Bard Act would not be applied to create a preservation law until 1965, civic leaders knew about the law and spoke of its application long before the New York City Landmarks Law was drafted. The Municipal Art Society recognized the potential for the Bard Act as enabling legislation and, beginning in 1959, initiated efforts to amend the City’s zoning code, pushing for application of the law in “some kind of aesthetic zoning.”

Leaders of Greenwich Village were aware of the Bard Act and even corresponded with Bard on possible applications of the law. A group of Village leaders suggested using the Bard Act to enact aesthetic zoning to protect the Village's neighborhood character. In 1959, many Villagers testified at the City Planning Commission's public hearings to support including historic and aesthetic protection in a new zoning resolution.

In Brooklyn Heights, leaders of the Community Conservation and Improvement Council (CCIC) were delighted to learn of the Bard Act as they sought a means for legal protection of the Heights' architecture and community character. The knowledge of the Bard Act's existence inspired CCIC to seek protection for its architecture in terms of a free-standing historic district, beginning in the late 1950s as part of the new zoning resolution.

- The 1955 veto jacket, the 1956 bill jacket, and the 1968 amendment to the bill can be found at the Science, Industry and Business Library of the New York Public Library, 188 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016.

Minutes from the meetings of the Joint Committee on Design Control can be found in the Professional Papers of Robert C. Weinberg, Long Island University.

The Albert S. Bard Papers

Archives and Manuscript Division

New York Public Library

Fifth Avenue at 42nd Street

New York, NY 10018

Albert S. Bard and the Origin of Historic Preservation in New York State, by Carol Clark. - Oral Histories with Frank Gilbert and Otis Pratt Pearsall

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Tel: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org